As high school graduation draws near, teenagers everywhere are lost. Although their expectations are out of date and they are not well-informed about their actual professional alternatives, they have a strong interest in future jobs.

That’s what the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s latest study says. About 690,000 kids aged 15 and 16 from over 80 nations, including the US, participate in the poll. The report’s five main findings are as follows:

-

Roughly 4 out of 10 students are unclear about their career expectations, double the number from about a decade ago.

-

Almost half (49%) agree (35%) or strongly agree (14%) that school has done little to prepare them for adult life.

-

There s a gender gap in students aspirations to work in sectors like information technology and health care. For example, around 11% of boys report that they will work in information technology at age 30, compared with 1.5% of girls.

-

Job preferences focus on a few, well-known professions, such as teaching, psychology and sports. For example, around half of girls and 44% of boys report that they expect to work in one of just 10 jobs, with little change in career preferences since 2000.

-

The majority of young people don t get connected to workforce professionals who can help them understand the opportunities available to them. Only 35% report attending a job fair, and just 45% visited a workplace.

The report has a Teenage Career Readiness Dashboard, arranged by eight themes, that covers almost two dozen concerns and enables cross-national comparisons:

Uncertainty about one’s career: Do pupils have clear plans? Is it important? According to the survey, behaviors like disengagement from school are influenced by career insecurity.

Planning: What are the expectations for students’ jobs? Have they evolved throughout time? How do they stack up against the real need from employers? Resources for career planning are especially inaccessible to low-income pupils.

Misalignment or alignment: Do students know what they must do to fulfill their career goals? Many teenagers have out-of-date or unrealistic job objectives, giving priority to a small number of high-status professions while ignoring in-demand technical careers.

Aspirations: Does a student’s social background influence their educational plans more than their aptitude? According to the report, aspiration levels are strongly influenced by socioeconomic status. Compared to their richer peers, low-income kids are less likely to see themselves in professional professions, making the disparities especially pronounced.

Advice: Do students take part in career counseling programs that improve their lives? The majority say they have little access to career counseling, and the consistency and quality of that counseling vary widely.

Career development: Do students receive adequate assistance that addresses socioeconomic inequalities? Although underutilized, career fairs, job shadowing, and internships are essential. The United States has the fifth-lowest rate of any country surveyed, with about one out of five students reporting speaking with a career adviser outside of school.

Future anxiety: To what extent do students believe they are ready for their future careers? About half (47%) concur that they are concerned about their readiness for life after school.

Employer involvement: How can employers support career development and educational initiatives? Does this change anything? When it comes to giving students access to career development opportunities like internships and job shadowing, the United States falls well behind of other nations examined.

Recent survey data from Gallup, the Walton Family Foundation, and Jobs for the Future underscore this, showing that young Americans increasingly feel lost when they move from high school to the next phase of their lives. More than 1,300 Gen Zers aged 16 to 18 and their parents participated in this poll.

Less than three out of ten teenagers feel highly prepared to pursue any of the eight post-high school pathways, such as a certification program, a career, college, or the military, according to the survey. Less than half of students feel prepared to take the first step, even those who are most eager for a certain path.

Additionally, just slightly more than half of parents (53%) regularly talk to their teenagers about life after graduation, according to the report. Three out of four parents of seniors who will graduate in a few weeks have yet to have that discussion.

When conversations do take place, they usually stay in well-known areas, like a four-year university or a paid position. Teenagers’ knowledge reflects this limited perspective; roughly one-third of them say they are well-versed in full-time employment or bachelor’s degrees.

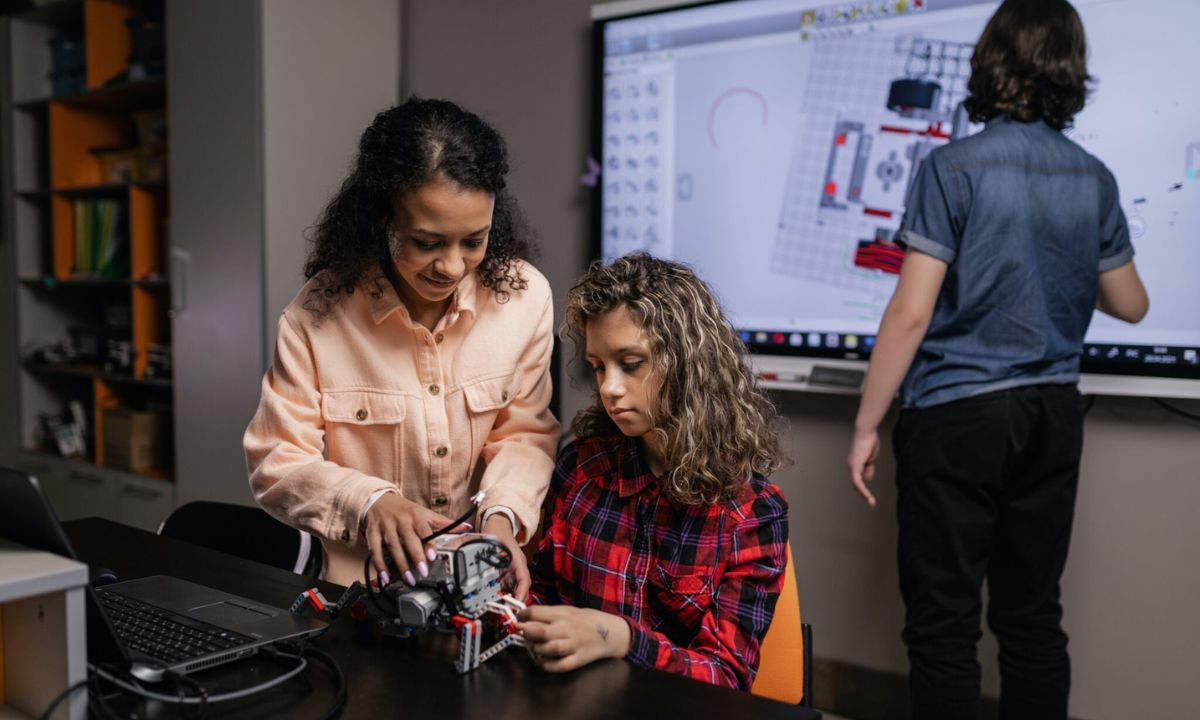

According to both research, young people struggle to properly navigate life after high school because of at least two career-launch issues. The first is an exposure gap; too few students know what employment alternatives are out there or know how to get there. The second is a lack of experience, since too few youth participate in work-based programs like internships or apprenticeships that enable them to relate their education to the workforce.

Students are unlikely to develop the skills, networks, and professional identity necessary for success as adults if they are not exposed to or experience employment possibilities. Students who remember talking to career professionals or taking part in work shadowing are much more likely to have career ambitions that are in line with the demands of the labor market, according to the OECD survey.

What then can advocates and leaders at the state and district levels do?

First, begin the official professional discussion as soon as possible. As early as middle school, the exposure and experience deficits should be filled. Young people are more prone to become lost in the transition from school to their next stage if they have to wait longer.

Second, expand career education’s reach. A menu that includes certifications, two-year degrees, skilled crafts, military service, and career and technical education should replace the emphasis on college.

Third, incorporate accountability into career training. Engage youth in meaningful, adult-like activities including paid employment, internships, and community service.

Fourth, assist parents. Parents and guardians can learn from a variety of programs and activities, such as workshops on careers in the local labor market or the various certifications and credentials that young people can obtain.

The Gallup and OECD surveys both serve as reminders of how crucial it is to incorporate career exposure and experience into young people’s regular school experiences. A key component of this treatment is a dose of real adulthood, which is given earlier, described more clearly, and practiced alongside the adults that teens are supposed to imitate.

The 74