Register right away.

The University of Chicago’s Behavioral Insights and Parenting Lab has been studying how parents make decisions for more than a decade. One important finding from our study is that parents’ actions do not always match their intentions. This gap between purpose and action may cause parents to be less involved with their kids, which might hinder the development of their skills.

This disparity is a typical feature of decision-making. Individuals make plans to prepare for retirement or follow diets, yet they frequently fail to meet their objectives. The stakes are bigger in parenting: skipping a preschool day or not reading a bedtime story may seem like little things at the time, but over time, these learning time gaps add up and make it harder for kids’ skills to catch up.

How can behavioral science assist parents in bridging the intention-action divide, and why do well-meaning parents occasionally find it difficult to engage their kids?

Our research finds workable solutions to close the gap, and behavioral economics provides insights into what causes intention-action gaps. Many of these strategies are based on the idea of nudges, which are little adjustments to the way options or information are presented that increase the likelihood that the desired action will be taken. Nudges in parenting frequently take the kind of digitally delivered reminders, comments, or other basic resources. These nudges recognize that busy parents aren’t neglecting their kids’ education because they don’t love them, know them, or have good intentions; rather, it’s because everyday life is full with obstacles and temptations.

According to our research, parenting decisions are heavily influenced by present bias, which is a manifestation of the intention-action gap. Like everyone else, parents frequently place more value on short-term gains than long-term gains. The advantages of today’s actions can be long-delayed, even if extensive research indicates that reading books to a toddler improves their language skills later in life. Meanwhile, weariness and everyday distractions require urgent attention.

Even when parents respect activities like reading, this tendency may lead them to prioritize the present over the future. By giving parents goal-setting reminders and text-message encouragement to read to their kids from a digital library we made available to parents, we addressed present bias in our Parents and Children Together (PACT) study. The purpose of these reminders was to bring the future into the present. Over the course of six weeks, parents who got these reminders read to their kids more than twice as often as parents who got the digital library without any reminders.

Interestingly, parents who showed present-biased preferences in pre-experiment assessments were the ones who benefited the most. Put another way, when we assisted parents in overcoming present bias, the parents who were most likely to put off reading the most showed the most benefits. The additional reminders didn’t much affect parents who weren’t biased because they already read on a daily basis.

Tools to Help Parents Follow Through

Our research lab’s Show Up to Grow Up project, a randomized controlled trial we carried out to boost enrollment in Chicago’s publicly supported preschool programs, is another effective illustration of reducing the intention-action gap. Over the course of 18 weeks, our intervention delivered parents customized text messages that highlighted the learning opportunities their child lost while not in school and the number of days their child had been missing. The messages served as a reminder to parents of their resolve to establish positive attendance practices and their objectives for assisting their kid in acquiring kindergarten-ready abilities.

When compared to children of parents who did not receive these messages, preschool attendance rose by roughly 2.5 school days for children whose parents received them, and chronic absenteeism—defined as missing 10% or more of the school days in a school year—decreased by 20%. Parents’ activities were in line with their long-term objectives thanks to the text’s nudges and reminders. This kind of light-touch program is a promising strategy for education policymakers looking to lower early absenteeism because it is affordable and simple to grow.

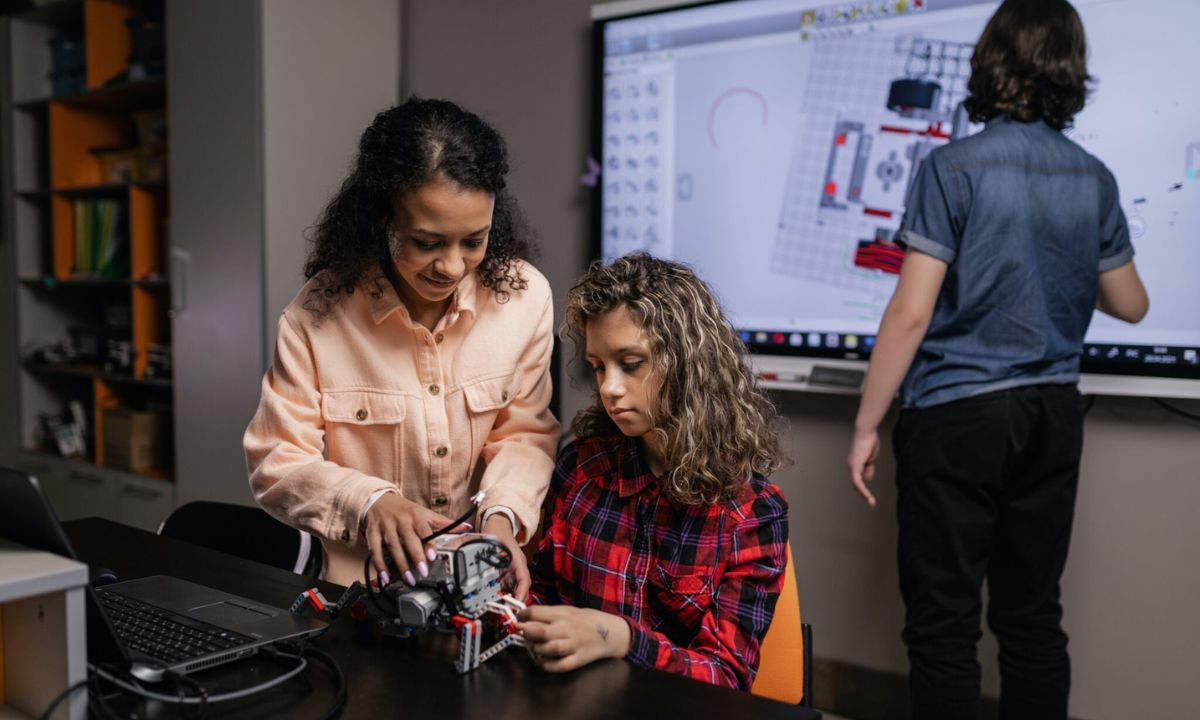

One promising way to reduce the intention-action gap is through technology. A tablet loaded with more than 200 excellent children’s books was given to families as part of our most recent Children and Parents Engaged in Reading (CAPER) project. To cut down on distractions, the tablet didn’t have any apps or internet connection outside of the library. The objective was to make group reading as simple and entertaining as possible while removing the challenge of discovering new books.

There was a noticeable effect on the verbal abilities of the kids. From roughly the 41st to the 50th percentile nationally, low-income children whose families had access to the digital library over the course of an 11-month trial demonstrated about 0.3 standard deviations more progress in language skills (equivalent to three months of language learning) than those who did not. Notably, for parents who showed present-biased preferences in tests given prior to the experiment (as in the PACT study), the treatment impact was significantly larger (by 0.50 standard deviation), which is equivalent to roughly five months of language learning on the test we gave children. Reducing obstacles to the intended activity can occasionally be the most effective strategy for closing the intention-action gap.

From Research Insights to Early Childhood Policy

Beyond academia, these research findings provide a new set of tools for early childhood policy. Conventional parenting programs frequently make the assumption that parents will behave in a certain way if they are given free resources or information about the advantages of their choices. However, resources and information by themselves don’t necessarily result in a change in behavior, particularly when cognitive biases are present.

The intention-action gap can be immediately addressed by behaviorally informed, relatively inexpensive treatments. To promote habits like daily reading, conversations, or preschool attendance, for instance, text-message programs can be scaled through school districts, pediatric clinics, or social assistance organizations.To guarantee that families have access to books and find them convenient and pleasurable to use, digital tools, like the library tablet used in the CAPER study, might be incorporated into public early education programs or library efforts.

By concentrating on parents who experience more cognitive biases or for whom these biases cause the greatest harm, such initiatives can advance equity. Research indicates that the best and most economical moment to empower parents as active partners in their children’s development is before they enter kindergarten, and behavioral techniques can help address early learning disparities before then.