Yvette Medina frequently accompanied her father to the bank to cash cheques while she was growing up in the Central Valley work camps in California.

You ought to work as a bank teller, he would tell me. Medina recalled, “You spend your entire day indoors, away from the sun.” Growing up, I didn’t have many options or goals to strive for. My parents simply had no idea what was going on.

All that changed with a program called Mini-Corps. As a component of the state’s Migrant Education program, Mini-Corps provides language tutors to labor camps and schools to assist children whose parents are employed in California’s dairy farms, timberlands, fisheries, and agricultural fields. Medina attributes her success in high school and her college enrollment, where she eventually obtained a teaching credential, to Mini-Corps tutors.

However, on July 1, President Donald Trump withheld grant funds from the Migrant Education program, defunding it, at least temporarily.A number of other educational initiatives, such as teacher professional development, English learner programs, and after-school centers, were also discontinued. The reduction in California came to over $810 million.

In order to make sure public funds are used in line with the President’s priorities and the Department’s legislative obligations, the U.S. Department of Education stated that it would not distribute the funds until it had finished reviewing the programs. It only released the after-school grants last week.

When that review would take place was not specified by the department. California and twenty-three other states have filed a lawsuit, arguing that Trump had no authority to withhold the funds because Congress had already funded them.

There are Migrant Education programs in practically every Californian county. With almost 5,000 migrant students, Kern has the most, although even major cities like San Francisco have a few dozen. Programs for such pupils have now been reduced or suspended. While some school districts managed to scrounge together funds to continue the activities over the summer, others terminated staff and stopped programs completely. The cuts resulted in the layoff of more than 400 employees at the Butte County Office of Education, which manages the state’s Mini-Corps program. In addition to terminating numerous services for migrant students, such as college visits, a math and science program, a debate contest, and summer programs, the Santa Clara County Office of Education lay off 22 employees.

According to Tad Alexander, deputy superintendent of the Butte County Office of Education, “we hope that we find some other finding source.” However, it seems like they are attempting to bleed it out at the moment.

On the move with the harvest

According to a recent study by the educational research and development group West Ed, nearly 80,000 Californian pupils are migrants who relocate with their parents every few months for employment. That might entail the harvest of oranges in Porterville during the winter, strawberries in Salinas during the spring, peaches in Madera during the summer, and almonds in Oroville during the fall. Some families even travel to Mexico in between harvests or to Washington during cherry season. According to WestEd, most migrant farm workers are permitted to reside and work in the United States.

Some migrant students are not registered in school at all, even though the majority attend classes at least occasionally. They are either assisting their family in other ways, taking care of younger siblings, or working in the fields themselves.

Academic difficulties are common among migrant students, many of whom are English language learners. Just 16% and 24% of students who are enrolled in school, respectively, fulfilled the state’s math and English language arts standards last year.

However, in part because of the Migrant Education program, migrant students had comparatively high graduation and college-going rates, mainly attending community colleges. In addition to one-on-one tutoring, students can receive assistance with reading, math, science, English language proficiency, health, and social-emotional support. They can also receive assistance with college enrollment and adjusting to life beyond high school.

The United States has provided services and safeguards to foreign farm workers for almost a century. Beginning in 1942, the United States and Mexico entered into an arrangement known as the Bracero program, which let Mexican laborers to lawfully work in American agricultural areas. President Lyndon Johnson took over after that program expired in 1964 and implemented a number of other initiatives that helped migrant workers, such as the historic Migrant Education program and the Immigration and Nationality Act.

Johnson had taught in a school along the Texas-Mexico border early in his career, when the majority of his pupils were immigrant children. He established groups for sports and literature, assisted in teaching them English, and took them to other towns for speech and athletic contests. He purchased playground equipment with his first payday.According to the National Archives, Johnson’s other anti-poverty initiatives from that time period, like the Migrant Education program, were inspired by that event.

One of the smallest federal education programs, the Migrant Education program served roughly 270,000 kids countrywide last year. Migrant Education is the least expensive of all the programs that Trump cut funding for on July 1st, costing $121 million in California and $375 million nationally.

Dark times

According to Debra Benitez, director of migrant education services for WestEd, the program’s defunding has had a chilling effect on migrant families worldwide. According to her, the majority of immigrant families place a high importance on education and are prepared to make significant sacrifices so that their kids can attend school. That is made possible by the Migrant Education program, she said.

Benitez, whose ancestors were migrant workers in the San Joaquin Valley, stated, “This is a population of people who have dedicated their lives to agricultural labor, very difficult work which we know historically no one else is willing to do.” Their only want is for their kids to receive an education.

Because immigrants are so important to the farming, dairy, fishing, and other businesses, she thinks that cutting off financing for migrant education will eventually harm the economy.

These families’ situation has long been difficult and demanding; they have historically been migrant farm laborers. However, Benitez stated that they are honored to support the California economy. The human aspect of it comes next. It hurts. These seem like gloomy times.

Bilingual teacher pipeline

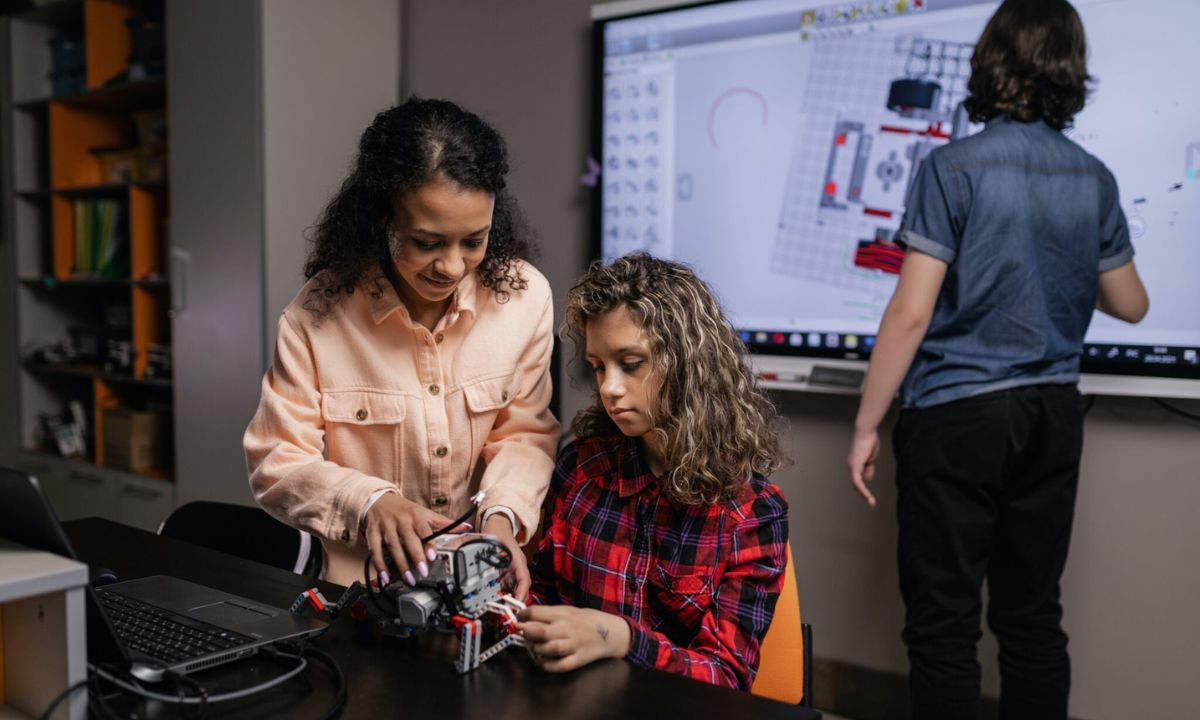

Mini-Corps works with 28 colleges and universities in the state to train tutors to work in schools and camps. In addition to earning $17.25 per hour, tutors can acquire classroom experience that will help them in their future teaching career. The majority speak Spanish fluently, but some California migrants speak Punjabi, Chinese, Hmong, and other languages.

The goal is to develop a pool of bilingual instructors while simultaneously assisting immigrant children.

While attending Cal State San Marcos, Daniel Martinez-Osornio served as a Mini-Corps tutor for migrant children. He worked at Vista and San Marcos schools, assisting pupils with their coursework while also fostering relationships and assisting children in avoiding social rejection, he claimed.

Martinez-Osornio, who grew up in Salinas, was aware of the difficulties experienced by migrant pupils. While many of his friends and cousins moved for jobs, his family did not. With more than 4,300 migrant students, Monterey County has one of the highest percentages of migrant students in the state.

I am aware that it is difficult. The parents are working all day, and kids have to be home to take care of their siblings or be taken care of by siblings, he said. The kids just want someone to talk to about their day, what s going on, express their feelings. They just want to have some happiness.

Martinez-Osornio was so inspired by his work in the Mini-Corps program that he decided to become a teacher. He recently earned his credential at Stanford and hopes to be a bilingual elementary teacher in Salinas.

He was shocked when he heard that the federal government stopped funding the program.

It breaks my heart, he said. I just couldn t believe it, considering the impact it has on kids and families. It s generational impact.

Waiting and hoping

Some counties have been able to salvage their summer migrant programs without laying off staff, at least for now. The Fresno County Office of Education, which has the state s third-largest migrant program with 6,300 students, has converted half of its summer programming to a hybrid virtual format. Instead of two weeks at an outdoor education camp called Scout Island, students will spend one week there and one week on other activities, including online learning.

Fresno County Superintendent of Schools Michele Cantwell-Copher said her office would continue to help migrant students as best it can, but it will likely have to make deep program cuts.

(This program) is a lifeline for thousands of students in Fresno County, she said. The students who are impacted by cuts to migrant services are the same students whose families put food on our tables. We will continue to advocate fiercely to ensure these young people get the support they deserve.

Imperial County, which has 3,543 migrant students, received nearly $5 million last year for its migrant education program. Nonetheless, the county doesn t plan any layoffs or program cuts, in part because County Superintendent of Schools Todd Finnell said he s confident that the federal money will come through eventually. Also, the program is worth keeping even without the federal resources, he said.

Our students and families benefit significantly from the program and any reduction or elimination would certainly be a loss in our mission to improve the quality of life in Imperial County, Finnell said.

Hope that you didn t have before

Yvette Medina, whose parents are laborers from Mexico, moved every few months as a child. Her parents picked cherries, tomatoes, watermelon, asparagus and apricots, sometimes working in packing plants in Stockton or Tracy. Medina didn t spend an entire year at one school until her senior year in high school, when she stayed with an aunt in Manteca.

Mentors in the Migrant Education program helped her enroll at Sacramento State, and inspired her to become a Mini-Corps tutor herself.

In a world where you feel lost, it s another person who speaks your language, reflects your culture, Medina said. They re in college, they re role models. You think, oh my gosh, I want to be like that too.

Medina worked as an elementary school teacher for several years after graduating, and now runs the Mini-Corps program at the Butte County Office of Education. In addition to running that program, the office oversees Migrant Education for 22 counties between Sacramento and the Oregon border.

Mini-Corps changed my life, it changed my family s life, Medina said. It introduced me to a profession where I d have access to a salary, benefits, networks. It gives you hope that you didn t have before.