Victoria Gomez de la Torre is unsure of whether or when the migrant children she works with will receive the educational support they have grown to depend on.

Gomez de la Torre is in charge of 12 counties in central Florida’s migrant education program. Children of migratory agricultural laborers, who relocate within and between states according to planting and harvesting seasons, benefit from the federally supported program.

Her team locates migrant agricultural laborers and assists them with school enrollment for their kids. Additionally, it facilitates their access to healthcare and tutoring.

More than $6 billion in education financing, including funds for migrant education, after-school programs, English-language instruction for non-native speakers, and other grants, was frozen by the Trump administration earlier this summer. The administration stated that it wished to evaluate the initiatives, even though Congress had previously approved the funding.

The administration unfrozen $1.3 billion of the funds earlier this month and said last Friday it will release the remaining $5.5 billion.

However, the harm was already done to Gomez de la Torre’s program, which had to close this summer without funding.

Joram Rejouis, the director of program development for the public schools in Alachua County, the largest of the 12 counties and home to Gainesville, stated, “We didn’t have enough money left over to carry the program.” Undoubtedly, the software was damaged when it was stopped.

When 11 employees of Gomez de la Torre were offered new jobs within the school system, the initiative was shut down. Approximately five dozen migrant children in the twelve counties were not receiving summer services throughout the month of July. Prior to the beginning of the month, the funds were expected to be disbursed.

“It’s going terrible,” Gomez de la Torre remarked. Families of migrants rely on us, our system, and our assistance.

Throughout the year, the Alachua County program provides services to between 1,000 and 1,200 migrant worker children, many of whom live in rural farming towns. Programs in Florida help about 17,000 migrant children annually.

According to Rejouis, the initiative is extremely beneficial for a population that is quite susceptible. Undoubtedly, the families, the program, and the district suffered harm as a result of the program’s termination.

Children of migrants are more likely to experience health issues like anemia and high blood pressure, and they are less likely to receive regular primary care. There is a shortage of food for many migrant families that work in the fields.

Additionally, the service facilitates communication and translation between guidance counselors, instructors, and parents. “Whenever they needed something, they came to us,” Gomez de la Torre recalled. They no longer have us.

The funding suspension exacerbated the apprehension and anxiety brought on by the Trump administration’s more general actions to target immigration benefits. Recently, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services declared that Head Start will henceforth be excluded from the list of public programs available to illegal immigrants. Senior officials stated following the funding announcement earlier this month that the administration had put in place safeguards to make sure the money wasn’t used against Executive Orders.

“Who knows when we’ll return?” Gomez de la Torre replied. if we return. If individuals who made the decision to retire decide to return, their retirement may be revoked. Nobody can predict with certainty how it will turn out.

California is experiencing a similar situation.

The Butte County Office of Education, located north of Sacramento, oversees the statewide Mini Corps program, which pairs multilingual tutors with migrant children at work camps and schools to assist them during the school day. According to Yvette Medina, the program’s coordinator, many of the tutors are themselves former migrant children.

According to spokesperson Travis Souders, the office had to let off over 400 employees throughout the state due to the funding freeze. The group is awaiting official written notice before reversing layoffs, despite Friday’s declaration.

According to Medina, a large number of kids will simply face more challenges on top of the ones we currently face.

Medina said the program had to completely shut down in Santa Clara County, which includes San Jose.

Growing up in a migrant labor camp, Medina followed her parents to the fields at 4 a.m. to pick grapes and cherries before school. Her folks worked all across the Central Valley, back in Mexico, and all the way up to Oregon on the West Coast.

“Destructive,” she remarked. I am positive that I would not have completed high school if it weren’t for the migrant program.

As the Trump administration increases immigration raids and arrests—which President Donald Trump maintains are targeted at people with criminal histories—migrant families are already experiencing anxiety.

According to Gomez de la Torre, they are afraid. Families stopped sending their children to school, while others left the nation.

Ruby Luis was a migrant child herself and now works as a consultant for school districts around Florida to identify and enroll migrant students. Her parents were employed at produce-packing houses, strawberry and Christmas tree farms, and orange orchards.

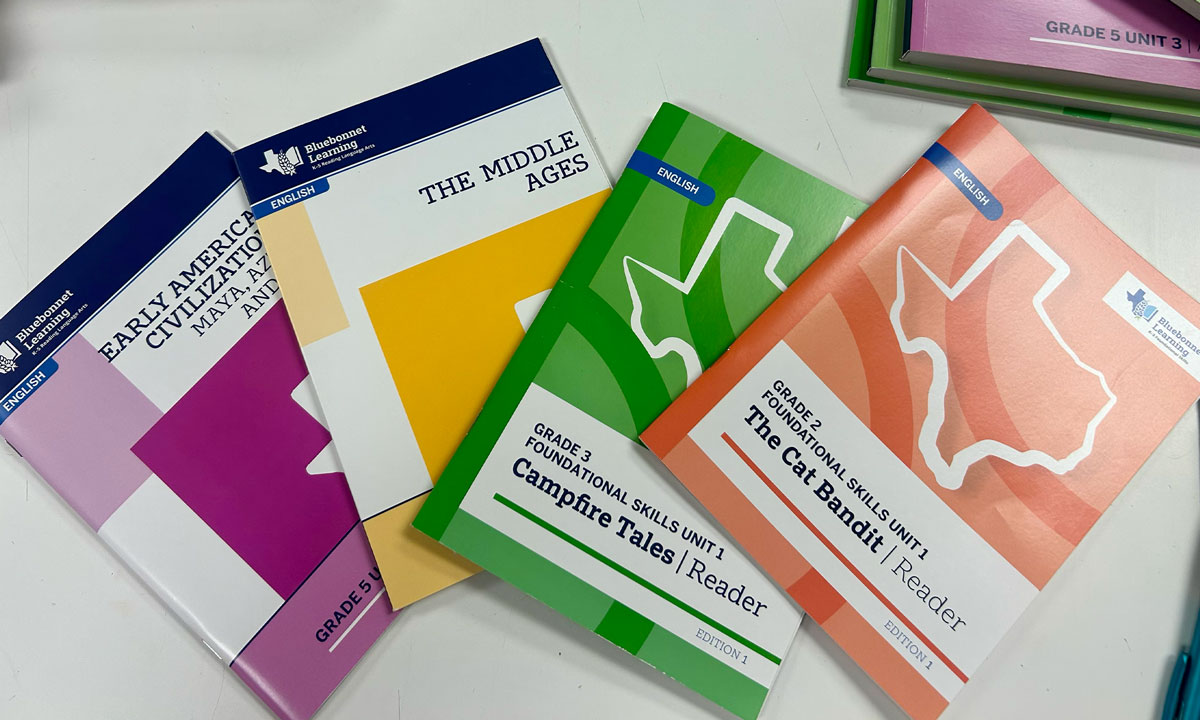

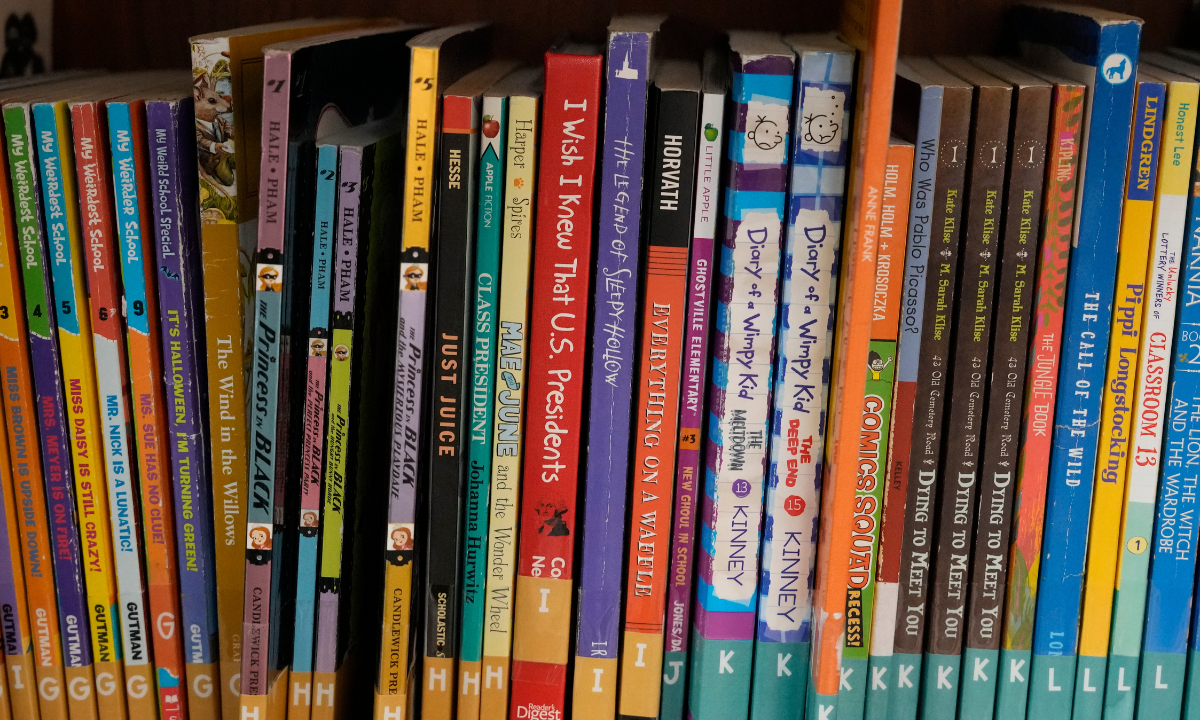

She received school supplies and books from program tutors. She participated in the program’s college tours and enrolled as a first-generation college student through a scholarship for migrant children. She ultimately received a biology degree upon graduation.

“You don’t have anybody to talk to about [that], so it’s just having even someone to talk to about going to college,” she said. That support had a significant influence.

According to Luis, taking it away and leaving them to handle it alone puts up these obstacles. Additionally, it may eventually prevent these kids from receiving an education.