Students from southern Indiana’s Crawford County Middle School suffered academically in the wake of the pandemic, just like their counterparts around the country. Tarra Carothers, the principal, understood her children needed assistance to get back on track.

She therefore made the decision to double the amount of time spent teaching English and math two years ago. These vital disciplines are now taught to students twice a day. A significant trend supports Carothers’ belief that the shift has been successful: from 2024 to 2025, Crawford’s ILEARN English language arts scores rose by more than 8 percentage points.

However, when it comes to English, Indiana middle schools are often moving in the other direction. According to state exam results, middle schoolers are actually having more difficulty in English than children in lower grade levels, even though they have made progress in arithmetic. The seventh and eighth grade ILEARN English proficiency percentages have decreased since 2021, with the decline being more noticeable for seventh learners. Additionally, sixth graders’ performance decreased over the past year, even if their scores are somewhat higher than they were four years before.

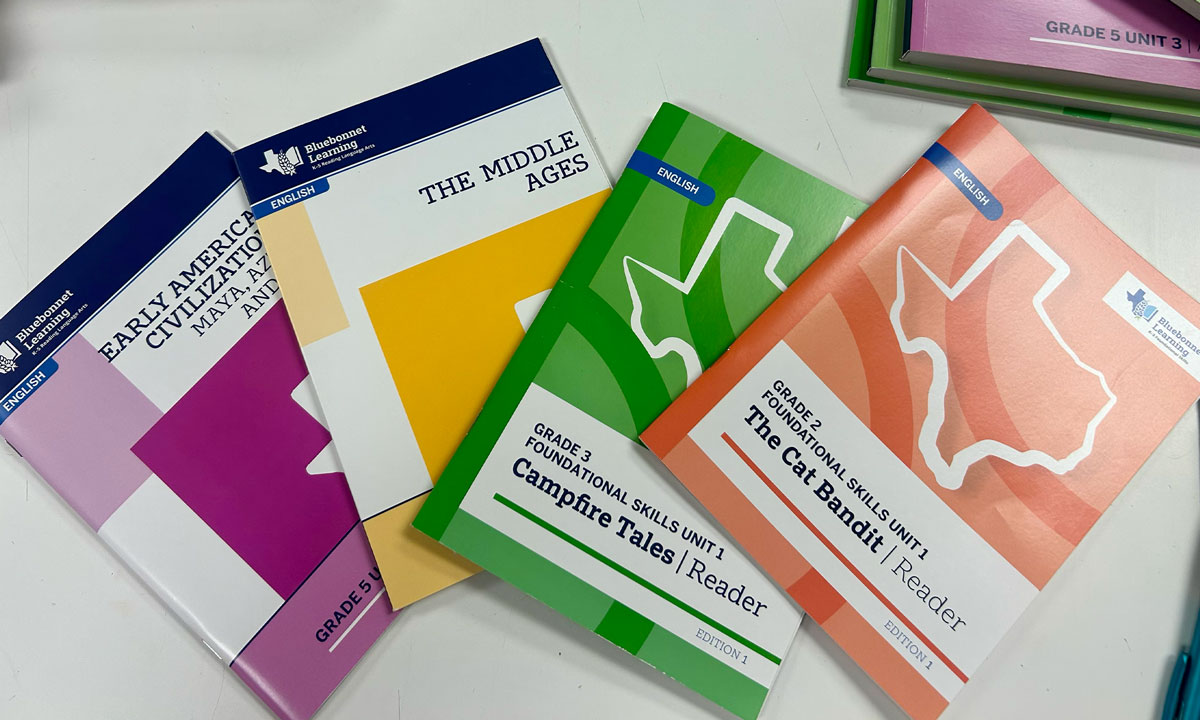

Like many other states in recent years, Indiana has made large and widely reported expenditures in early literacy, mostly focusing on the science of reading. For today’s middle school students, however, that change in instruction has come too late. While this development has been patchy, third and fourth students’ ILEARN English scores have increased by comparatively little since the pandemic.

At a meeting on July 16, the Board of Education voiced particular worries regarding the performance of middle school students. Secretary of Education Katie Jenner stated, “We need to take it up and make sure all of our middle school kids are reading and provide those extra supports.”

Some middle school administrators claim that their tactics can improve the situation. They highlight involvement in a pilot that permits students to take ILEARN multiple times throughout the academic year rather than only once in the spring, in addition to lengthening the amount of time spent teaching important subjects. According to educators, using these checkpoints can help children receive data-driven reflection and remediation, which improves test performance.

Middle school an optimum time for students recovery

“I frequently ask teachers if middle school students seem different since the pandemic, and they nod,” said Katie Powell, director for middle level programs at the Association for Middle Level Education. According to Powell, these middle school students who are recovering from the epidemic are more difficult to engage and inspire, self-report higher levels of stress, and are less inclined to take academic risks.

They were in school and just beginning to establish basic reading and math fact fluency when the pandemic struck, she said. For example, when the pandemic closed schools, current eighth students were in second grade, and many spent a large portion of their third grade year learning online. According to Powell, pupils should cease learning to read in the third grade and begin reading to learn instead.

According to Powell, middle schoolers are going through a period of rapid development where their bodies and brains are changing the most compared to infancy.

According to her, now is the best moment to intervene and support them. There is yet time. However, it’s imperative that we focus on them right now.

Students at Crawford County Middle School spend two times each in math and English during the school’s nine daily periods. Although many schools use some form of block scheduling, many others use a format where students attend classes only every other day. At Crawford, however, kids show up for every class every day. Their type of block scheduling doubles the amount of time spent on math and English teaching.

There had to be sacrifices made in order to accomplish this change. There was less time for other subjects because periods were cut. Carothers was concerned about a decline in student performance in science and social studies. However, she said that the opposite happened. For instance, despite children spending less time in the science classroom, sixth grade science results rose, according to Carothers.

“They will perform better in social studies and science if they have better reading and math skills,” she said.

In contrast, the first three periods of the day at Cannelton Jr. Sr. High School, which is located on the Kentucky state line, last 90 minutes instead of the usual 45. During these first three periods, each student has either math or English, providing for twice as much time in class as usual.

Last year, Cannelton’s English language arts ILEARN scores for grades six through eight rose by over nine percentage points.

Schools use more data to track student performance

Brian Garrett, the principal of Cannelton, thinks that his school’s new method of obtaining data and its dependence on it are both secrets.

In order for teachers to monitor their progress and identify knowledge gaps, students take benchmark tests early in the school year, usually within the first two or three weeks.

The state is using that approach for all of its schools this year. Students will take variations of ILEARN three times instead of once near the end of the year, with a condensed final exam in the spring. More than 70% of Indiana schools participated in the state’s ILEARN checkpoint pilot program last academic year.

The Indiana Department of Education anticipates that checkpoints will help instructors and family make sure a student is on track all year long and make the exam results more actionable.

According to Kim Davis, principal of Indian Creek Middle School in rural Trafalgar, ILEARN checkpoints, in conjunction with teacher reflection and focused remediation efforts, helped us inform instruction all year long rather than waiting until the end of the year to see if students had truly mastered the material based on the state test.

Indian Creek teachers were able to modify their curriculum by using the checkpoints to determine which standards the pupils were having trouble with. Additionally, students benefited from having more experience with the test; they could see how the questions will be formatted for the spring final exam.

According to Davis, it was incredibly educational for the teachers yet felt very pressure-free.

It also affects what kind of data is collected. According to James Tutin, principal of Eastwood Middle School, Washington Township middle schools previously employed the NWEA, an exam that was administered several times during the year, to gauge student learning. Although the NWEA was a useful tool for tracking development, the results did not always correspond to what a student would score on an exam such as ILEARN because it did not meet Indiana state criteria.

The district switched to ILEARN checkpoints last year and collected weekly data using a service called Otis.

During a class time, students had around six minutes to respond to a few questions with data that teachers could then enter into Otis. Teachers were able to focus their instruction during the intervals between ILEARN checkpoints thanks to that data.

In order to ensure that we don’t wait until the checkpoint to find out how our kids are likely to perform, Tutin stated that in addition to receiving practice through the checkpoints, they were also receiving highly targeted feedback on a daily and weekly basis.

Davis and Tutin emphasized that only assigning students to take the checkpoint ILEARN assessments was insufficient; teachers also needed to reflect and work together, encouraging one another to pose difficult questions and assess their own instruction.

Davis stated, “We’re not satisfied with where we are; we still have a fire inside of us to grow further.” However, it’s extremely thrilling that we’re moving in the correct way.