While funding is important in education, it does not ensure that students will succeed.

For instance, consider New York. The Education Law Center modified school spending statistics in relation to their local labor market prices in its most recent study, “Making the Grade.” The total amount of money provided to public schools, the distribution of those monies among schools, and the amount spent in relation to the state’s gross domestic product per capita all received an A rating for New York’s school finance system.

All things considered, New York’s school funding structure was ranked among the best, if not the best.

Despite this, New York pupils’ performance is marginally worse than the national average. In Fiscal Year 2022, its pupils’ overall performance in fourth-grade math on the National Assessment of Educational Progress’s Nation’s Report Card fell, despite the fact that its schools spent $33,970 per student, $15,509 more per student than the rest of the nation.

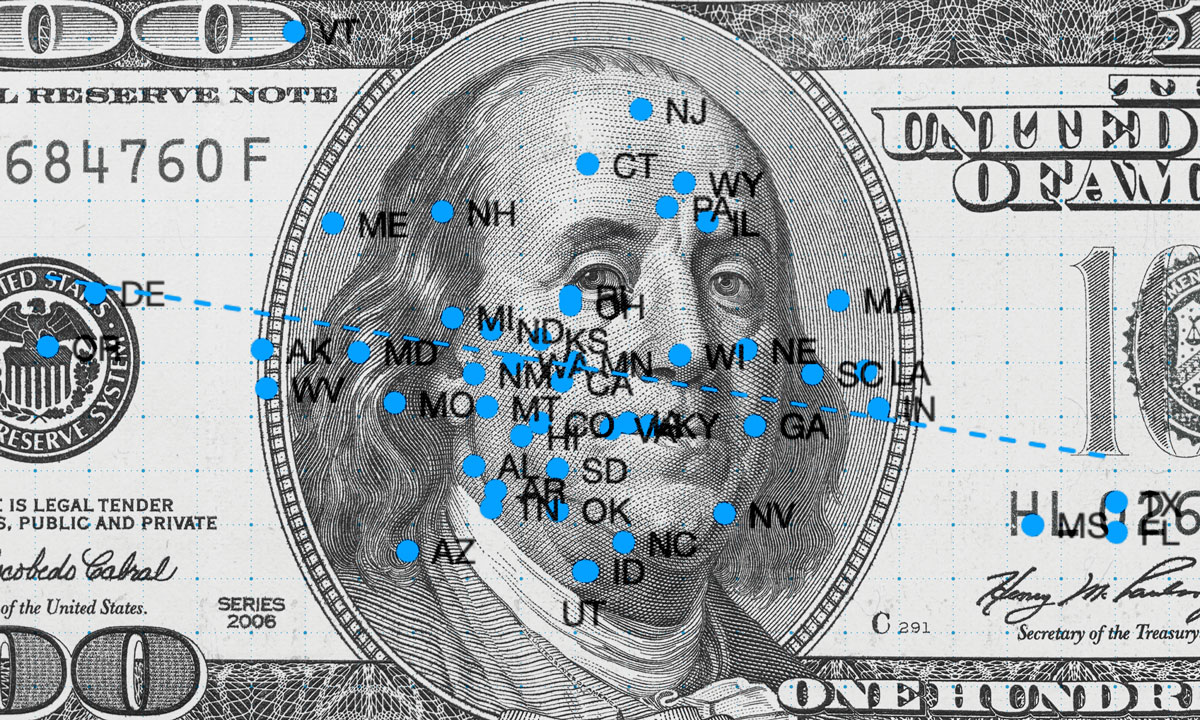

It’s not limited to New York, though. Contrary to popular belief, there is little correlation between student results and school investment. I used the Education Law Center’s spending statistics, which account for variations in cost of living, and the Urban Institute’s demographically adjusted NAEP results to create the most equitable comparison.

The results for 2022, the most recent year for which comparable spending data are available, are displayed in the graph below. New York is an extreme outlier, as you can see, as it spent more than any other state and had the lowest results. Considering their commitments, other high-spending states like Connecticut, New Jersey, and Vermont all saw quite unsatisfactory outcomes.

On this metric, which states perform well? Despite spending relatively little, Texas, Florida, and Mississippi all stand out for achieving excellent student outcomes.

How about the number of employees? The majority of school funding is allocated to salaries and benefits because education is primarily a people industry. However, there is also little correlation between personnel levels and student outcomes.

The graph below compares the same demographically adjusted fourth-grade arithmetic scores as before with the number of staff members per 500 kids in a typical elementary school. Vermont and Maine stand out in this regard since they have incredibly high personnel levels but no evidence of improved student results. In the meantime, states with high student test scores but low staffing numbers include Florida, Texas, and Mississippi.

Readers should not take these ideas too far because they are only correlations. For instance, in a recent analysis, Matt Ladner, a senior adviser at The Heritage Foundation, argued that states with the largest spending increases over the past 20 years did not have similarly significant advances in attainment. However, if state politicians determined that schools in, say, Vermont or New York, needed to reduce staffing or spending, it would hurt students in those states.

This is because the greatest evidence on school budgets indicates that a $1,000 increase in annual spending per kid raises college-going rates by 2.8 percentage points and improves test scores by 0.008 standard deviations. Similar, albeit modest, results were obtained with infusions of government ESSER monies. Although the improvements are so little that they cannot be easily seen on a chart, they are statistically significant and have academic significance. It is possible that no one was or is pleased with the size of the returns on increased spending for public schools. Furthermore, this study demonstrates that test scores actually increase as a result of school spending.Policymakers would be reckless if they ignored these broad patterns.

However, it is reasonable to point out that policy is not created in a vacuum and that the benefits of increased spending are minimal. Spending more might likely have a positive impact in some areas, particularly the Mountain West. In the meanwhile, more time spent considering cost-effectiveness and ways to promote improvements without extra funding might be beneficial in other locations, particularly in the Northeast.

Mississippi is the best example of the latter in the modern era. Ten or twenty years ago, Mississippi—the poorest state in the nation—would not have appeared as a positive outlier on these kinds of statistics. However, the state has implemented several policy changes since 2013, such as new curriculum materials, a strict school accountability system that targets the students who fall the most behind, and a third-grade reading requirement that draws more attention to kids who have basic skills issues. Even though some of these programs were expensive, their total impact on the state’s education budget was little, and they gave Mississippi children a significant advantage over their counterparts in states with higher spending levels.

When some supporters, even in states and localities with ample funding, are demanding more funding while others have exploited and continue to use the small gains from expenditure increases as justification for school choice or other reforms, it is difficult to engage these kinds of nuanced discussions. The only way for policymakers to properly comprehend the complexities of school spending is to acknowledge its importance while also being aware of its limitations.