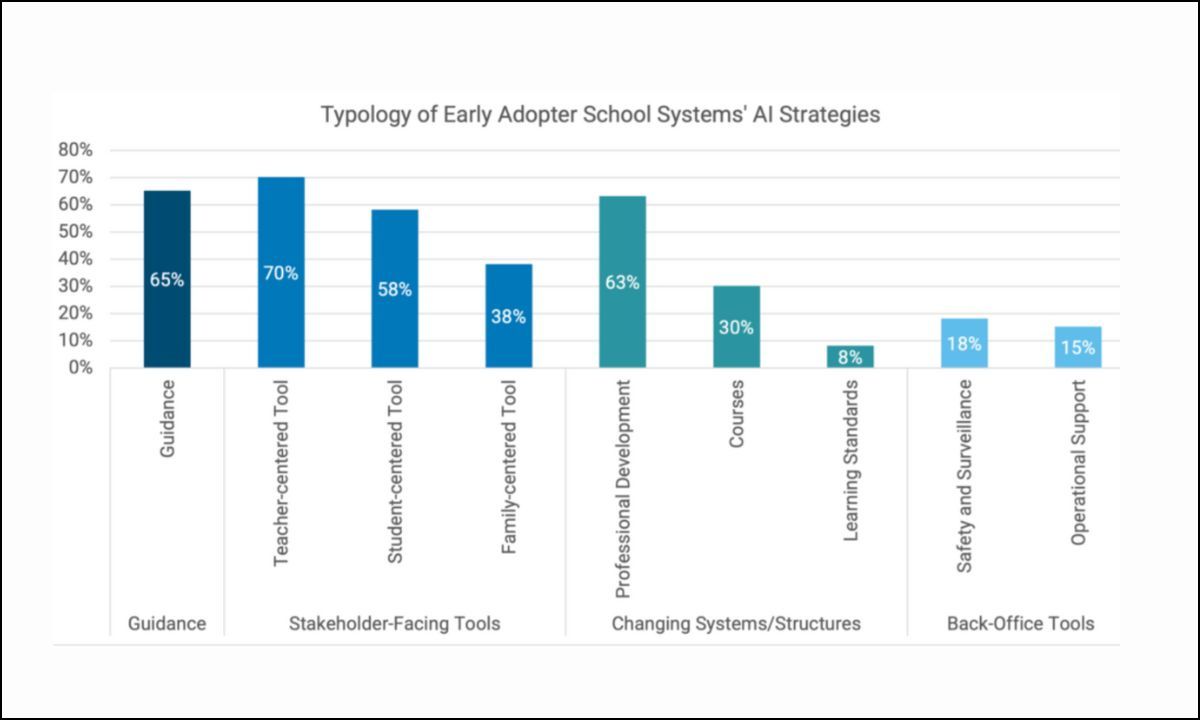

Districts nationwide are under pressure to advance artificial intelligence quickly, but haste without plan can backfire. AI has the potential to address long-standing issues in public education and increase opportunities if implemented properly. If done incorrectly, there is a chance that disparities may worsen and valuable resources that the most disadvantaged kids require to bridge opportunity gaps will be wasted.According to preliminary data, wealthy suburban school districts are roughly twice as likely as urban or rural ones with high rates of poverty to train their teachers in artificial intelligence.

Our researchers heard from numerous of district officials in the Center on Reinventing Public Education sAI Early Adopter study who are striving to find the ideal balance between acting quickly and remaining rooted in equality, transparency, and their primary goal of teaching children. In order to prepare their children for the upcoming AI-based industry, those leaders believe that districts should take their time and determine what families and parents desire. In order to determine whether their strategies are effective, they need also monitor district development and ensure that AI initiatives benefit underserved children.

This begins with being aware of AI’s potential and pitfalls, particularly the risks associated with prejudice and false information. In order to ensure that everyone has a basic understanding of these tools and how they operate, leaders must also collaborate with families, educators, and students to learn about AI and establish common objectives. Districts are accomplishing this through task forces, school-based AI education sessions, and community discussions with their superintendents.

Families placed a high value on being prepared for the workforce of the future, according to Gwinnett County Public Schools, a diverse district west of Atlanta, which started extensive community involvement in 2017. By speaking with experts and leaders in the field, the district was able to steer discussions on artificial intelligence’s role in education and eventually develop a district-wide plan for its application. New K–12 AI literacy standards, an AI-focused high school, and advice on how to develop literacy, handle bias and privacy issues, and assess generative AI tools like ChatGPT were all part of this.

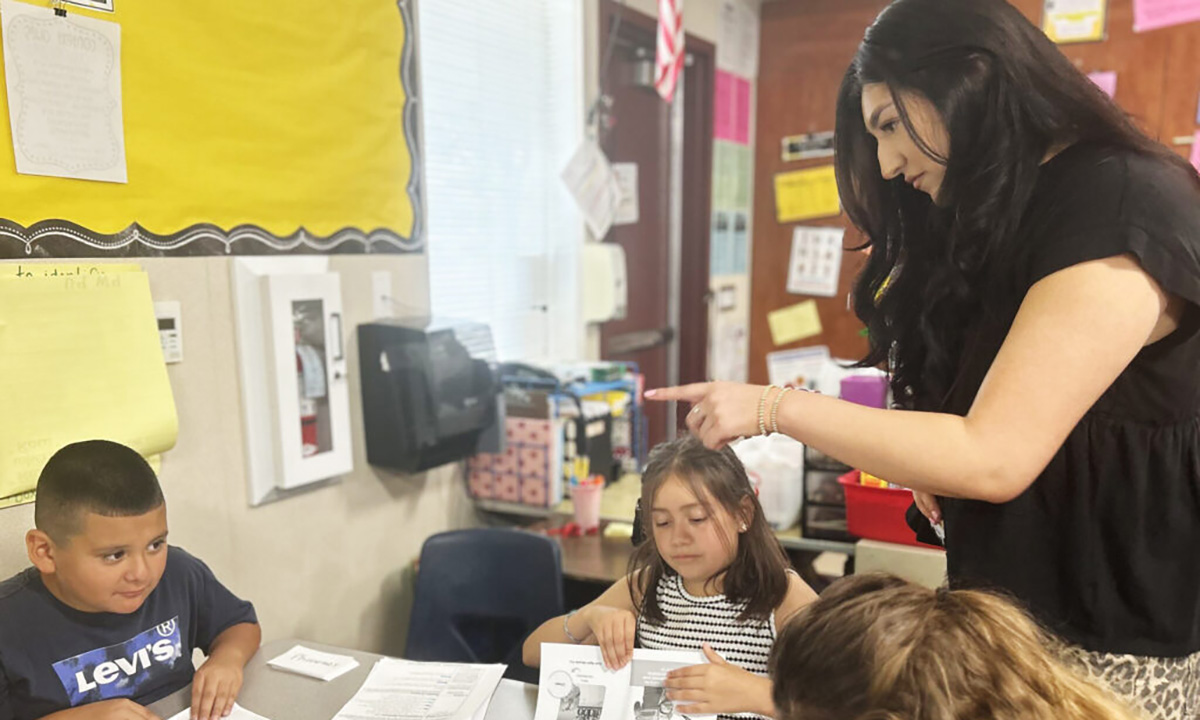

According to CRPE study, well-thought-out plans are the key to successful AI deployment. Teachers refuse to use AI in the classroom if they do not see how it can help students, even though schools and districts ultimately decide if and how kids can use the technology. Even though they could have access to professional development and apps, this is nonetheless the case. In order to implement AI-enabled strategies, such as providing multilingual learners with educational technology apps that facilitate translation or automating lesson planning to free up teachers’ time to engage with students, Early Adopter districts that have witnessed the greatest use of these tools by educators and students begin by analyzing their strategic plan.

A task force was established by the Santa Ana Unified School District in California to investigate how AI can help the district’s multicultural readiness purpose, instructional and equitable goals, and Future-Ready Learning framework. The end result is an AI Compass that guarantees the technology is utilized in line with district-wide principles, such as student welfare and academic integrity. The compass, for instance, states that the district would create an honor code for artificial intelligence and teach kids how to utilize it as a learning tool rather than as a replacement for their own work.

Districts can promote safe practices by implementing short, low-stakes trials that can be turned back if they don’t work, in addition to involving the community and ensuring that AI use serves larger objectives. To have a better understanding of the variable and necessary conditions needed for effective implementation, they can test across a range of schools. To lower risk, use small-scale pilots that evaluate various options and are simple to shut down. Additionally, they enable slow-moving districts to confirm if new AI tools truly lessen teacher workloads or improve student learning.

Ultimately, unless districts are able to monitor where AI is assisting and where it is not, it will not enhance learning. To enable educators to observe what is changing, this entails developing data systems that link tools, platforms, and insights across schools. Currently, too much important information like student interests, attendance, and tests is spread across several apps that aren’t able to communicate with one another. As a result, educators and district administrators are unable to fully understand how AI is benefiting or harming pupils. Additionally, those who require this data frequently cannot access it. AI techniques are merely educated guesses in the absence of integration.

In order to prevent already underprivileged pupils from falling further behind, districts should have a well-defined data plan. Without a plan to reduce gaps, investing in AI runs the risk of providing more opportunities for well-resourced children to engage with the technology than for historically excluded students, therefore perpetuating the very disparities that districts are trying to address.

AI was used by the Issaquah School District in Washington state to close the achievement gaps that still exist for children with disabilities, Latino or Hispanic pupils, and Black or African American students. Issaquah, which is based on Universal Design for Learning techniques, uses AI-powered educational technology to let students finish tasks in a variety of formats, including textual responses, voice recordings, video slideshows, and other forms of expression. Through professional development and the selection of AI tools and resources, Issaquah is pursuing a multi-year strategy to harness emerging technology to help reduce chronic achievement gaps.

When applied effectively, AI can assist in addressing long-standing issues such as assisting multilingual children, students with disabilities, and students who are below grade level. However, this is only possible if leaders remain laser-focused on helping these students rather than pursuing glitzy tools. To guarantee inclusive and equitable use of AI in education, EdTrust has pledged to listen to stakeholders’ needs and desires over the course of the next two years.

However, many districts cannot afford to accomplish this task alone, and they shouldn’t have to. In order to assist districts in using AI technologies, states and the federal government will need to take the lead. To help schools safeguard student privacy and prevent unforeseen harm, states should first establish clear guidelines for the use of AI. In order to ensure that all districts, not just the wealthiest, can create what they need, they should also set up financing streams for AI preparation, such as assistance for updating data infrastructure. Additionally, they should hold vendors responsible for making sure their solutions don’t exacerbate opportunity gaps or perpetuate bias. To ensure that all students, irrespective of location or financial status, can take advantage of AI-enhanced education, states and the federal government must likewise increase access to personal computers and bandwidth.

The government and corporate sector may invest millions to help guarantee that all kids, not just the wealthy few, are prepared for a new, AI-driven future and economy if they can afford to invest trillions in AI-powered technologies.