Congressmen’s requests to reinstate academic merit in college admissions may appear to be a neutral idea at first.

We believe that these ads conceal a concerted attempt to target diversity and access in American colleges and soften cherry-picked information.

As academics who research higher education access, we have discovered that these initiatives amount to a reversal of inclusive practices when combined with calls to bring back standardized testing.

According to a February 14, 2025, Department of Education letter to congressional offices, it is illegal for educational institutions to stop using standardized testing in order to improve racial diversity or attain the appropriate racial balance. Additionally, the letter asserted that the SAT and ACT, the two most popular admissions exams, are impartial assessments of merit.

We examined over 70 empirical research regarding the SAT and ACT’s roles in college admissions in our most recent peer-reviewed paper. Our research revealed a number of problems with these tests’ operation, particularly for students from historically underrepresented backgrounds.

Measuring college readiness

Reversing test-optional practices that were adopted during the COVID-19 epidemic, a number of prestigious universities, including Yale, Dartmouth, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, have reintroduced SAT or ACT requirements.

Discussions concerning how well these tests assess students’ intellectual readiness and how universities need to consider them when making admissions decisions have been rekindled by these modifications.

Some witnesses at a hearing of the U.S. House Subcommittee on Higher Education and Workforce Development on May 21, 2025, contended that test scores enable universities to admit students on the basis of merit. Test results, according to some, may act as obstacles to pursuing further education.

According to our research, these tests are not as valid as some claim, even though they are statistically reliable—that is, they yield consistent results for students across subjects and across numerous attempts under comparable circumstances.

Generally speaking, high school GPAs are a greater indicator of a student’s success in college than either test.

Furthermore, the assessments are neither fair or equally predictive for every kid, particularly when considering socioeconomic, racial, and gender demographics.

This is due to the fact that they consistently give preference to people who have greater access to good education, secure financial circumstances, and chances to interact with test-prep instructors and programs. It can cost thousands of dollars to prepare for the test.

In summary, privilege tends to be more reflected in both tests than potential.

For instance, on the SAT and ACT, students from wealthier families consistently perform better than their peers.

Given that wealthy households can afford private tutoring, test prep services, and exam retakes, this is not surprising. Higher scores, admission to prestigious universities, and scholarship chances are all made possible by these benefits.

Low-income kids, on the other hand, frequently encounter difficulties including less qualified teachers and restricted access to advanced placement, science, and math classes that do not take test scores into account.

Reflecting deep inequities

We discovered in our published review that these differences are systemic rather than incidental.

Long-standing evidence of bias in test design and disparities in average scores based on race, gender, and linguistic background were exposed by our review.

Inequities that influence how students study for and perform on these examinations are reflected in these results, which go beyond academic disparities.

Additionally, we discovered that high school GPA is a better indicator of college achievement than standardized examinations. Years of work, performance in the classroom, and instructor comments are all captured by GPA. It shows how students handle difficulties in the actual world rather than just how well they do on a timed test.

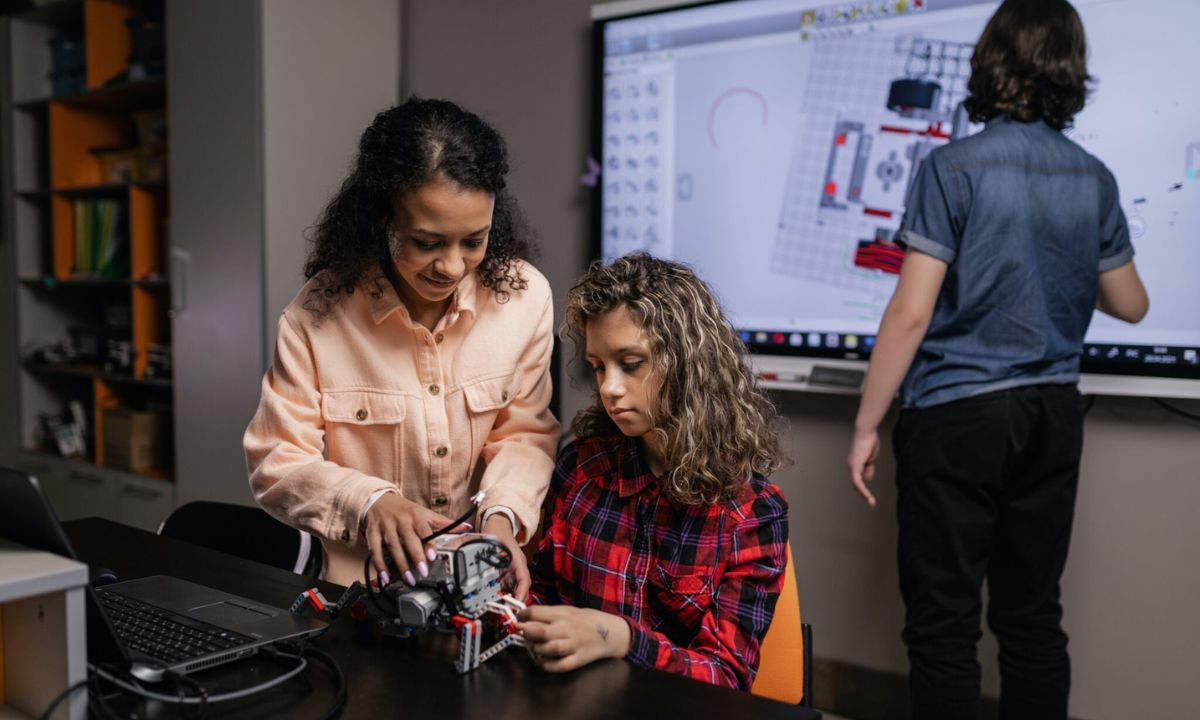

For a lot of students, especially those from historically underrepresented groups, grades can provide a more accurate picture of their readiness for work at the college level.

This issue is significant since admissions decisions are value statements rather than merely technical assessments. Selecting to base admissions on test results encourages particular types of preparation, experiences, and expertise.

Equity, according to the American Council on Education, is the ability to succeed. It entails creating learning settings that value the various types of potential and provide every student with the tools they need to succeed.

It’s important to keep in mind that studies on testing frequently concentrate on prestigious universities, where results from standardized tests are more frequently utilized as crucial screening criteria. Even at prestigious institutions, assessments’ ability to predict college academic performance is frequently restricted (moderate in statistical terms), according to our systematic review.

However, the majority of college students enroll in public regional universities, minority-serving schools, state universities, or universities that accept the majority of applicants. Standardized test results are even less reliable indicators of students’ performance at these institutions, according to our research.

This could be due to the fact that public regional universities and state universities are more likely to enroll a wide range of students, including first-generation, older, and part-time students as well as those juggling work and family obligations.

Where does higher ed go from here?

Higher education is at a crossroads in the argument over the use of standardized tests in the admissions process. Will universities forsake equity and give in to political pressure and limited notions of merit? Or will educational establishments reaffirm their purpose by adopting more comprehensive and equitable methods for identifying talent and assisting students in succeeding?

What values are prioritized will determine the answer.

Standardized tests should not be the gatekeepers of opportunity, as our research and previous studies have demonstrated.

Universities run the danger of denying talented students opportunities if they base their definition of merit solely on test results.