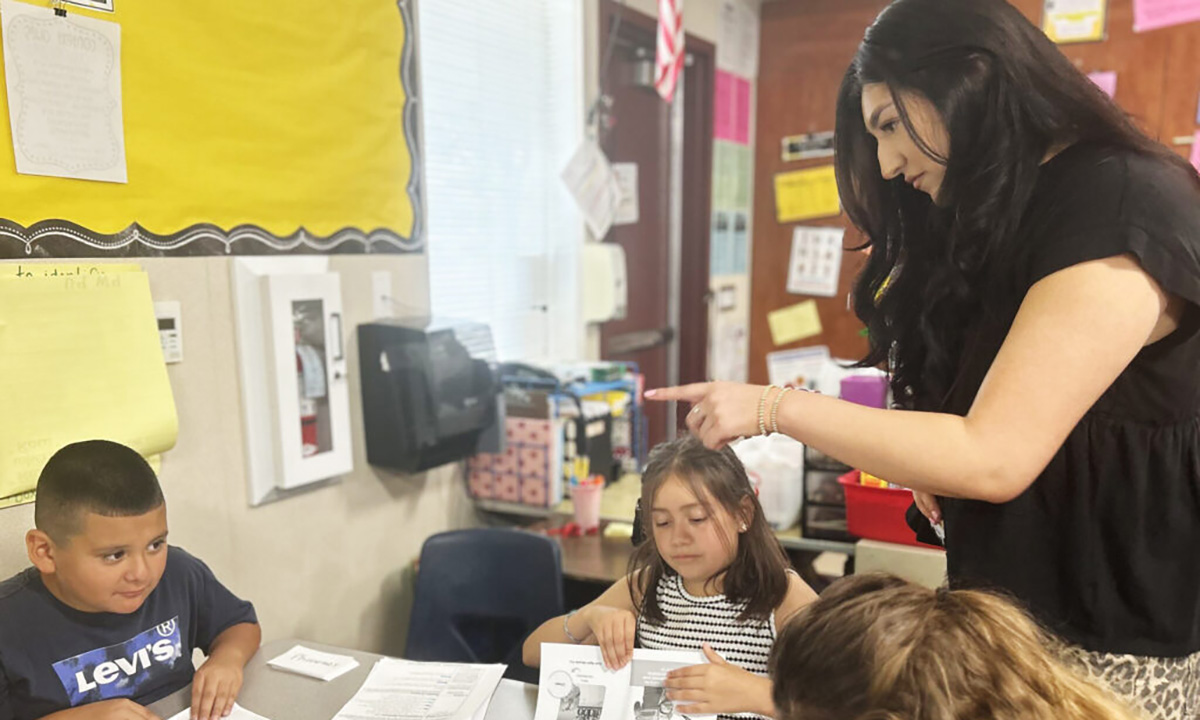

Following the U.S. Department of Education’s sudden announcement on Monday that it would not distribute almost $7 billion in education expenditures that Congress had already approved, children of migrant workers, English learners, and kids who rely on after-school care may no longer receive services.

The money, which states may typically receive by July 1, covers curriculum materials, teacher training, staff salaries, and other necessary costs. States and districts will therefore probably need to reduce those functions or find alternative funding sources. For instance, the postponement jeopardizes more than $1.3 billion in financing for 21st Century Community Learning Centers, which support educational institutions, libraries, and charitable organizations that offer enrichment and tutoring services.

According to Jodi Grant, executive director of the advocacy group Afterschool Alliance, we will soon witness an increase in the number of children and youth who are left unattended and in danger, as well as an increase in academic failures, hunger among youngsters, chronic absenteeism, dropout rates, and parents who are compelled to quit their employment.

In the midst of Trump’s continued efforts to close the department, the potential cancelation of more federal funding for schools exacerbates the chaos caused by the termination of current grants and contracts. Additionally, he would reduce more than $6.5 billion for 18 programs to a $2 billion block grant in his proposed fiscal 2026 budget. According to a meeting tape that was shared with The 74, Education Secretary Linda McMahon promised Western Governors Association members last week that Title I grants and special education money will be level funded for high-poverty schools. However, state leaders didn’t inquire, and she never brought up the other programs’ fate.

Despite the fact that the president signed the budget on March 15, Trump officials justified Monday’s action on the change in administration. According to the message, the department is still dedicated to making sure taxpayer funds are used in line with the president’s priorities and has not yet decided on prizes for the next academic year.

The action will undoubtedly lead to another lawsuit if the administration proceeds with reclaiming the money. The impact of earlier cuts has been lessened by federal courts. For instance, until 15 states and the District of Columbia obtained an injunction, McMahon attempted to revoke more than $2 billion in remaining COVID relief money.

In response, she said last week that all states with money left over should submit receipts for reimbursement once again to prevent issues with uniformity and justice.

The administration may withhold monies appropriated by Congress under the rarely used Impoundment Control Act, but the president must first obtain the consent of lawmakers, which he did not do in this instance. The head of the Office of Management and Budget, Russ Vought, informed senators last week that officials were thinking about a planto hold on funds meant for some agencies, but both Republicans and Democrats seemed dubious.

The top Democrat on the appropriations committee, Senator Patty Murray of Washington, said in a statement on Tuesday that the freeze will affect pupils in every ZIP code.

Russ Vought and President Trump must quit ruining our students’ futures and release these resources, she said. Local school districts cannot afford to make up the difference, especially not right away, or wait through drawn-out legal proceedings to receive the federal cash they are due.

Until the funds are released, some activists urged the Senate to postpone the Senate’s final approval of Trump’s nominations for the education department, such as Kimberly Richey to head the Office for Civil Rights and Penny Schwinn as deputy education secretary.

All4Ed, EdTrust, Educators for Excellence, and the National Center for Learning Disabilities were among the organizations who denounced the department’s action, arguing that it may have violated federal law and directly jeopardized the educational possibilities of our country’s most vulnerable pupils.

States are awaiting more than $2 billion to hire and train teachers, particularly for high-needs schools; about $900 million to assist English language learners; and $376 million for migrant education programs in addition to the financing for after-school activities.

Districts around the country will be hit hard, according to Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Beaverton, Oregon, and president of the School Superintendents Association, or AASA.

“This will be another unexpected cut to America’s public school system at a time when districts are already struggling financially,” he said. Budgets will need to be reorganized, and some staff positions may need to be eliminated, as school begins in a few weeks.

If districts find another way to cover expenditures this year, they may also forfeit their future eligibility to receive federal funding for such initiatives. Matt Colwell, who previously supervised federal programs for the Oklahoma State Department of Education, clarified that if a district uses state or local funding for a program, they do not require federal dollars to support it, according to the Every Student Succeeds Act’s supplement, not supplant rule.

“Once they commit to paying for it with state funds, the law severely restricts what they can do,” he said. He also questioned whether the monies were being held up because of staff layoffs. Investigating it could be a means of avoiding the statement, “We fired all the people who actually take care of this.”