According to an executive order issued by President Donald Trump on April 23, 2025, the United States is committed to fostering AI knowledge and proficiency among its citizens. The Advancing Artificial Intelligence Education for American Youth executive order makes it clear that increasing AI literacy is now a top national goal.

This poses a number of crucial queries, such as: What is AI literacy, who need it, and how can it be developed in a responsible and considerate manner?

The consequences of AI literacy—or lack thereof—are extensive. As stated in the executive order, they go beyond national aspirations to continue leading the world in this technological transformation or even to train a workforce with AI skills. Citizens and customers who lack basic literacy are ill-prepared to comprehend the algorithmic platforms and choices that impact several aspects of their lives, including news recommendations, government services, privacy, lending, and healthcare. Furthermore, a lack of AI literacy could allow a small number of multinational corporations to control significant facets of society’s destiny.

Therefore, how can organizations support people as individuals, employees, parents, innovators, job seekers, students, employers, and citizens in understanding, utilizing, or opposing AI? In our research, two educational academics and a policy scientist who focus on AI literacy examine these problems.

What AI literacy is and isn t

AI literacy is based on a combination of technical, social, and ethical knowledge, abilities, and attitudes. One well-known definition of AI literacy states that it is a collection of skills that allow people to utilize AI as a tool online, at home, and at work; critically assess AI technology; and interact and collaborate with AI in an efficient manner.

Programming, neural network dynamics, and prompt engineering—the process of meticulously crafting chatbot prompts—are only a few aspects of AI literacy.While employing AI to create software code, or “vibe coding,” may be enjoyable and significant, limiting the concept of literacy to the newest fad or corporate demands won’t be sufficient in the long run. Furthermore, too much variance makes it difficult to choose organizational, educational, or policy initiatives, even when a single master definition may not be necessary or even desired.

AI literacy: who needs it? Everyone, including the staff, students, and citizens coping with its increasing effects. Even though it’s not always obvious, artificial intelligence is now present in every industry and aspect of society.

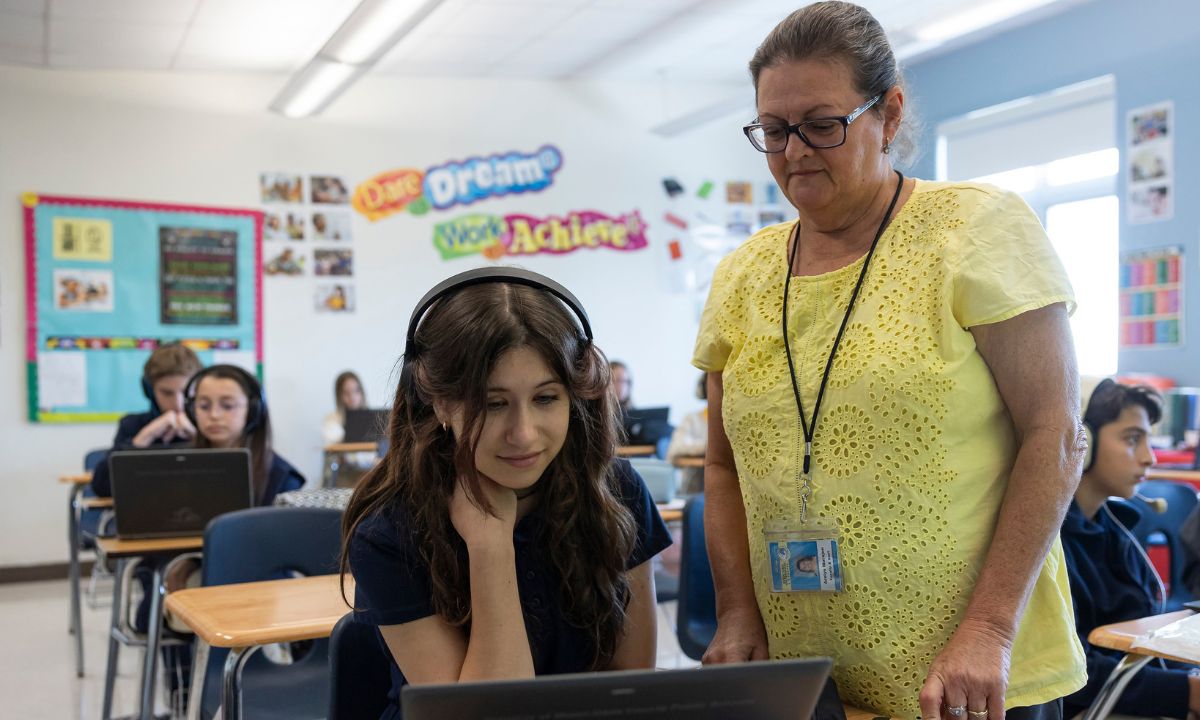

It’s far more difficult to determine how much literacy each person needs and how to get there. Do we need to integrate AI into K–12 curriculum, provide university micro certificates, and conduct practical workshops, or are a few brief HR training sessions sufficient? Researchers still have a lot to learn, which makes it necessary to gauge AI literacy and the efficacy of various training modalities.

Measuring AI literacy

Bipartisan agreement that AI literacy is important is emerging, but there is far less agreement on how to measure people’s AI literacy. Scholars have examined a variety of topics, including technical or ethical skills, various groups, such as students and corporate managers, or even subdomains like generative AI.

The great majority of the more than a dozen AI literacy questionnaires found in a recent review research rely on self-reported answers to statements and questions like “I feel confident about using AI.” Additionally, not enough research has been done to determine whether these surveys are effective for respondents from various cultural backgrounds.

Furthermore, the emergence of generative AI has revealed weaknesses and difficulties: Given how dynamic AI is, is it possible to develop a reliable method of measuring AI literacy?

We have attempted to assist in addressing some of these issues in our research partnership. To ensure that they accurately measure AI literacy, we have concentrated especially on developing objective knowledge evaluations, such as multiple-choice questionnaires that are subjected to extensive statistical analyses. A multiple-choice poll that we have tested so far in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany has proven to be reliable and equitable in all three nations.

Much more work needs to be done to develop practical and dependable testing strategies. However, in the future, only asking people to self-report their level of AI literacy is probably not enough to determine where various groups of people are and what kind of support they require.

Approaches to building AI literacy

AI literacy is being promoted by governments, academic institutions, and business.

In an effort to educate its citizens about artificial intelligence, Finland started the Elements of AI series in 2018.Tens of thousands of students and thousands of teachers will have access to AI technologies thanks to Estonia’s AI Leap initiative, which collaborates with Anthropic and OpenAI. Furthermore, China has gone further the recent presidential order from the United States by demanding at least eight hours of AI education every year, starting in elementary school. In order to prepare the next generation of AI leaders, Purdue University and the University of Pennsylvania have introduced new master’s programs in AI.

Notwithstanding these endeavors, these programs encounter an ambiguous and developing comprehension of AI literacy. They also struggle to gauge efficacy and have no idea of what teaching strategies are beneficial. Additionally, there are persistent problems with equity, such as accessing under-resourced or stretched enterprises, neighborhoods, schools, and demographic groups.

Next moves on AI literacy

We believe that a few actions would be wise based on our study, our experience as educators, and our cooperation with technology businesses and policymakers.

The first step in developing AI literacy is realizing that it’s not just about technology; people also need to understand its social and ethical aspects. Clear, trustworthy measures that monitor growth for various age groups and communities should be used by researchers and educators to determine whether we’re making progress. Through an autonomous hub, businesses and universities can test out new teaching concepts first and then share what works. To introduce AI into the classroom, however, teachers require the right tools and training—not just more courses. Additionally, partnerships that reach under-resourced schools and neighborhoods are crucial to ensuring that everyone benefits because opportunity isn’t distributed equally.

Importantly, developing universal AI literacy will likely be far more difficult than developing digital and media literacy, so it will take significant investment rather than reductions in research and instruction.

There is broad agreement that AI literacy is critical, whether it is to increase public confidence and adoption of AI or to enable citizens to question or influence its direction. We think it’s critical to approach AI literacy cautiously, avoiding hype or an unduly technical concentration, much like with AI itself. As the AI literacy executive order demands, the proper strategy may equip Americans to prosper in an increasingly digital world and train students to be engaged and responsible members of the workforce of the future.