In the fall of 2023, nearly 500 of Michigan’s 705 school districts announced a teaching vacancy. At the start of the 2012 academic year, there were 262 districts.

Since substitutes and inexperienced teachers who might have been employed to cover vacancies are not included in this figure, the number of openings is probably understated.

According to employment sites and local news reports, at least some Michigan districts are still having trouble filling vacancies for the fall of 2025.

Although the teacher shortage is a national issue, it is particularly severe in Michigan, where both the overall teacher shortfall and the number of teachers quitting their jobs are higher than the national average. Urban and rural populations, which have the most underfunded schools, as well as specialized fields like science, math, and special education, are especially affected by this scarcity.

My work at Michigan State University has focused on creating and overseeing successful teacher preparation programs for more than 20 years. My research focuses on how to assist people become successful classroom leaders in order to draw them to teaching and retain them in the field.

Low pay and lack of support

A number of variables contribute to teacher shortages, but in particular, low pay, excessive workloads, and a lack of continuing professional development are to blame.

For instance, according to a research published last year, teachers in Michigan and across the country earn roughly 20% less than people in other professions that also call for a college degree.

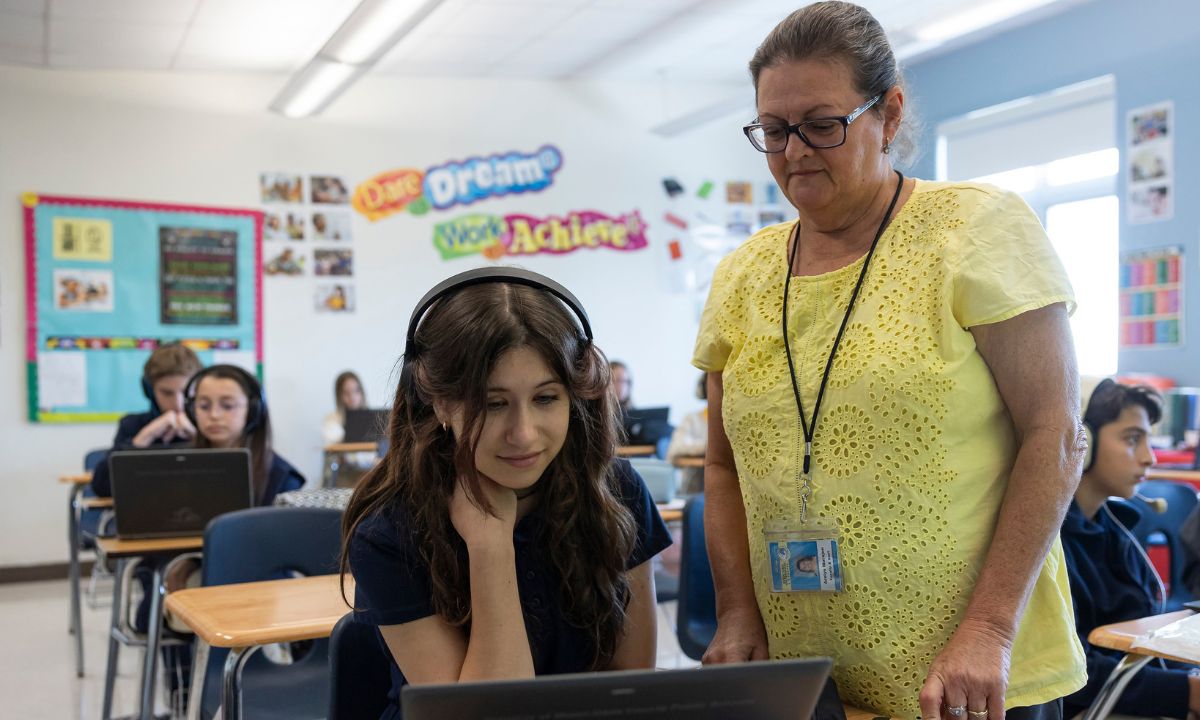

I’ve worked with educators and district administrators throughout the state, and I know that new teachers—especially those in places with acute shortages—are frequently assigned the most difficult assignments. Additionally, instructors in many districts have been compelled to work without the advantage of any planning time in their daily timetable.

The COVID-19 pandemic, which caused many educators to quit their jobs, made the shortage considerably worse. Another offender is the high number of teachers who were hired in the 1960s and early 1970s, when school enrollments skyrocketed, both in Michigan and nationwide, and who have been retiring in significant numbers over the last ten years.

Creating pathways to certification

Developing unconventional pathways to teacher certification has been one current tactic to overcome Michigan’s teacher shortage.

The goal is to more rapidly and affordably prepare teachers. These initiatives have received financial support from a range of Michigan Department of Education agencies, state-level grant programs like the Future Proud Michigan Educator program, as well as private organizations and corporations.

This approach has also been used by certain school districts, such as the Detroit Public Schools Community District, to certify instructors and fill open positions.

Partnerships between Michigan’s intermediate school districts, community institutions, and four-year universities and colleges have produced other programs of a similar nature. Grand Valley State University’s Western Michigan Teacher Collaborative, which focuses on college-age students who are interested, is one example. Another is MSU’s Community Teacher Initiative, which aims to encourage high school students to become teachers.

National initiatives like Teach for America and Teachers of Tomorrow are arguably even more well-known. While completing teacher training coursework, candidates in these programs frequently work as full-time teachers with little supervision or assistance.

Stuffing the pipeline is not the solution

However, filling the pipeline with new hires alone won’t address Michigan’s teacher shortage issue.

For teachers of color and those enrolled in unconventional training programs, the loss of instructors is noticeably greater. This begins during their certification preparation and lasts for a number of years following certification.

The lack of appropriate mentoring throughout the certification phase, the lack of instructional and other professional guidance in the early years of teaching, and a lack of understanding of the complexity of schools and schooling are the main causes of the increased attrition rates.

How to repair the leaky faucet

In what ways, then, may educators be motivated to remain in the field?

Scholars have discovered several ways to enhance the results of both conventional and alternative preparation programs.

Adjust expectations.Teaching is a vital profession, but it puts new teachers at risk for early burnout and departure by making them think they can undo the harm caused by a complex web of socioeconomic problems, such as multigenerational poverty and a lack of access to affordable, wholesome food, housing, drinking water, and medical care.

Provide dependable mentors to student teachers.Student teachers gain a deeper understanding of teaching as well as the relationships between schools, families, and communities via their work in schools. However, these experiences are only beneficial if they are supervised and encouraged by a knowledgeable and compassionate teacher and the organization’s leadership.

Understand the limitations of online education.While online programs for teacher preparation are useful and have their place, they don’t give student teachers practical experience or the chance to have a guided conversation about what they see, hear, and feel when working with students.

Honor the becoming process.After a new teacher has their official certification, their professional assistance should continue. Teachers require time to grow their abilities throughout their careers, just like other professionals like nurses, surgeons, and lawyers.

Giving teachers this support conveys a strong message that they are respected community members. Being aware of it keeps them in their positions.