Approximately one-third of pupils in schools across struggle to read at grade level. This dilemma affects both kids and teachers, even in Massachusetts, which routinely scores highly on a number of education-related indicators. Although some kids have always had difficulties, the COVID-19 pandemic increased these disparities and made it more difficult for many to catch up.

At Boston Collegiate Charter School, which educates 700 children in grades 5 through 12 from a socioeconomically and racially diverse student body, we witnessed this firsthand as an increasing number of students found it difficult to succeed in their English Language Arts classes. Our standard strategies of using a demanding curriculum and scaffolding grade-level books weren’t working as intended because many of the students were coming to our school lacking basic reading abilities.

We needed a fresh approach, and this year’s experiments and improvements taught us a lot about our children, our teaching, and what would be effective for other schools facing similar difficulties.

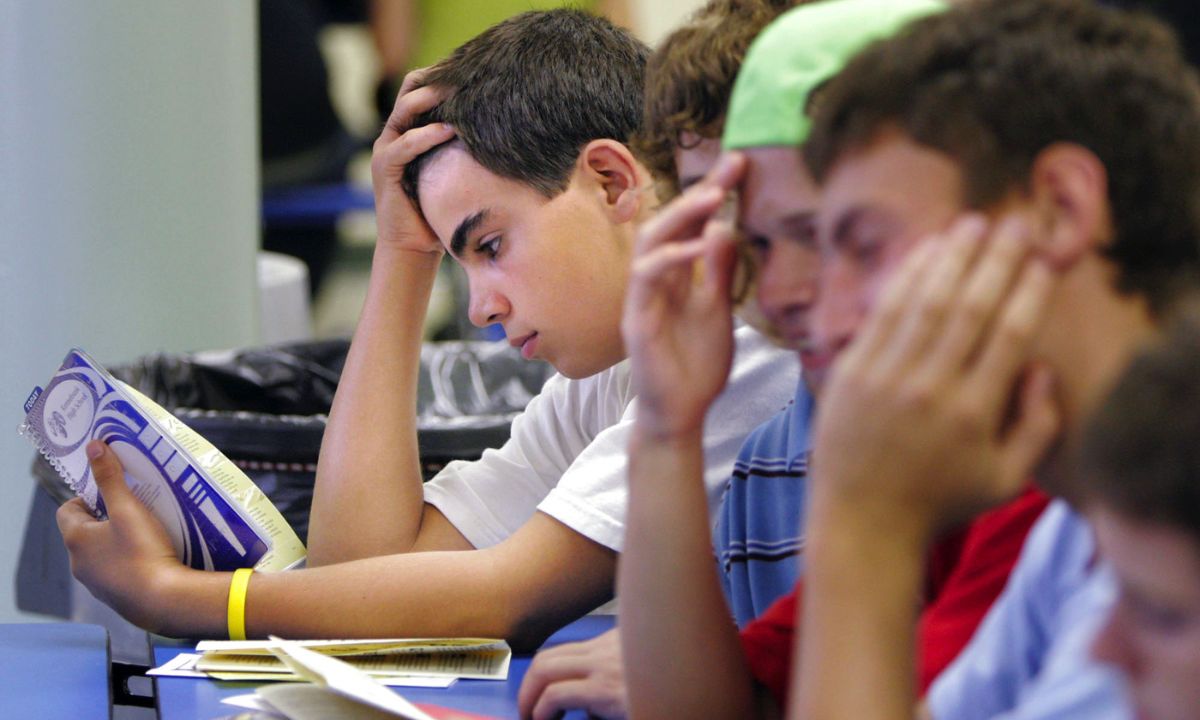

In our upper grades, the reading problems have gotten worse. Every year up to grade 10, we take in new pupils, and we’ve discovered that older pupils typically fall even more behind in their reading than those starting in fifth or sixth grade. For instance, some of the kids in our tenth-grade English class are reading and developing thesis statements about the nature of loyalty and power, while others are having difficulty understanding the meaning of the majority of the words on each page.

As a result, a Literacy Working Group comprising interested educators and school administrators was established last year. Finding ways to address the needs of our teenage students—particularly those who were falling well behind grade level—was our main objective. There is a wealth of literature on teaching reading to elementary school pupils, but there are significant gaps when it comes to teaching older students, as we discovered when we examined current research and teaching methods.

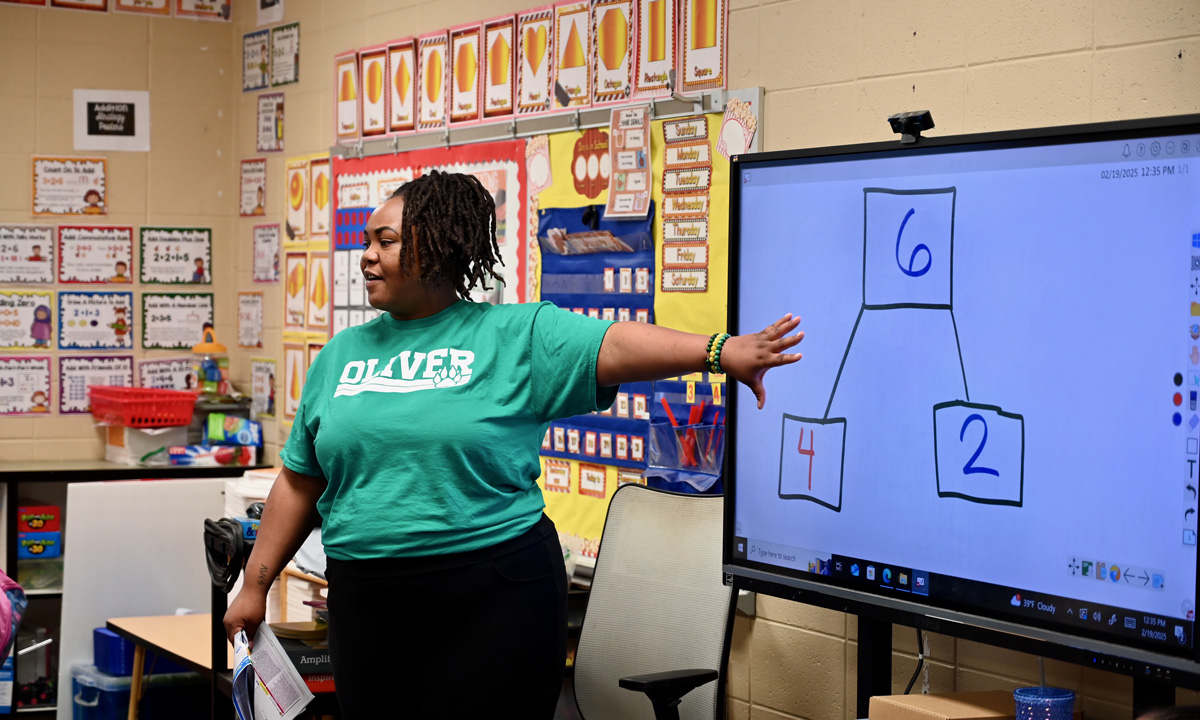

We began by delving into frameworks such as Scarborough’s Reading Rope, the Reading Comprehension Blueprint, and Keys to Literacy resources. These theories highlight the multifaceted nature of literacy: strong readers are the result of a combination of phonics, prior knowledge, vocabulary, syntax, and understanding. After determining the main areas that pupils needed to focus on, we enlisted the assistance of the whole school community.

We took a lot of time during our yearly staff orientation prior to the arrival of kids to build the foundation for why this literacy work is important and how all teachers, regardless of topic, can contribute. We discussed techniques and resources such as vocabulary deep dives, word preview activities, visual maps, and classification of word meanings.

We also considered school-wide programs, such as a word of the week, to help celebrate academic language and maintain literacy as a top priority, going beyond individual sessions. Through biennial teacher-led best practice showcases incorporated into our normal professional development calendar, we reviewed and reinforced successful tactics throughout the year. In addition to fostering consistency across grade levels and subject areas, these sessions gave instructors useful resources they could use right away in the classroom.

We implemented the REWARDS program, a structured, research-based intervention created especially for older kids, for those who required more extensive assistance with decoding and fluency. It emphasizes understanding techniques, fluency, affixes, and multisyllabic word recognition.

Although not all students were first thrilled to enroll, many started to notice noticeable improvements. A ninth-grader who had trouble understanding multisyllabic words had taught herself to practically skip them when reading, which limited her reading to fifth grade and made meaningful comprehension nearly impossible. She was able to begin decoding longer words thanks to strategies she acquired throughout the REWARDS intervention, and in a matter of months, she was reading almost at grade level. Her confidence changed along with her entire perspective on reading. pupils like this, who began the year farthest behind, are making the biggest progress, even though they are not typical of all pupils.

We’ve been using i-Ready, a diagnostic test that students take three times a year, to monitor development. In contrast to shorter, more frequent tests we previously employed, i-Ready has yielded more accurate information about kids’ starting points and development. Students’ success on the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS), which is a test that all students in the state must take in grades three through eight and ten, is strongly correlated with their test scores.

Students two or more grade levels behind were making more than a year’s worth of progress, according to i-Ready testing. Even while there are still some kids who fall well short of the standard, the gap has narrowed and they are now within striking distance of grade-level proficiency, which gives them newfound confidence and a genuine chance for long-term academic success.

Although literacy development takes time, we can make the modest but consistent progress that demonstrates real progress by providing teachers with the necessary tools and encouraging them to help students who struggle with reading. The advancements we have witnessed demonstrate what can be achieved when educational institutions adopt a collaborative, evidence-based strategy for promoting literacy among adolescents.

Even while early childhood reading skills receive a lot of funding and attention, we are dedicated to helping our students, who are adolescent learners who still require basic literacy support. They also deserve the focused, well-considered intervention that enables them to participate fully in their own education and read fluently.