“This is a quiet, devastating shutdown of a national institution.” So wrote Dr. Peggy Carr on July 14, describing the

hollowing out

of the National Center for Education Statistics. With only three staff remaining, the agency’s collapse marks just the latest national education data provider to disappear or degrade since the Trump administration served the U.S. Department of Education an

eviction notice

.

Now, as the department boxes up its pens and pencils, key responsibilities are scheduled for scattering to

unlikely corners

, from Health and Human Services to the

Small Business Administration

. Amid this reshuffling of federal furniture, however, one critical detail has been neglected: Who will track student outcomes?

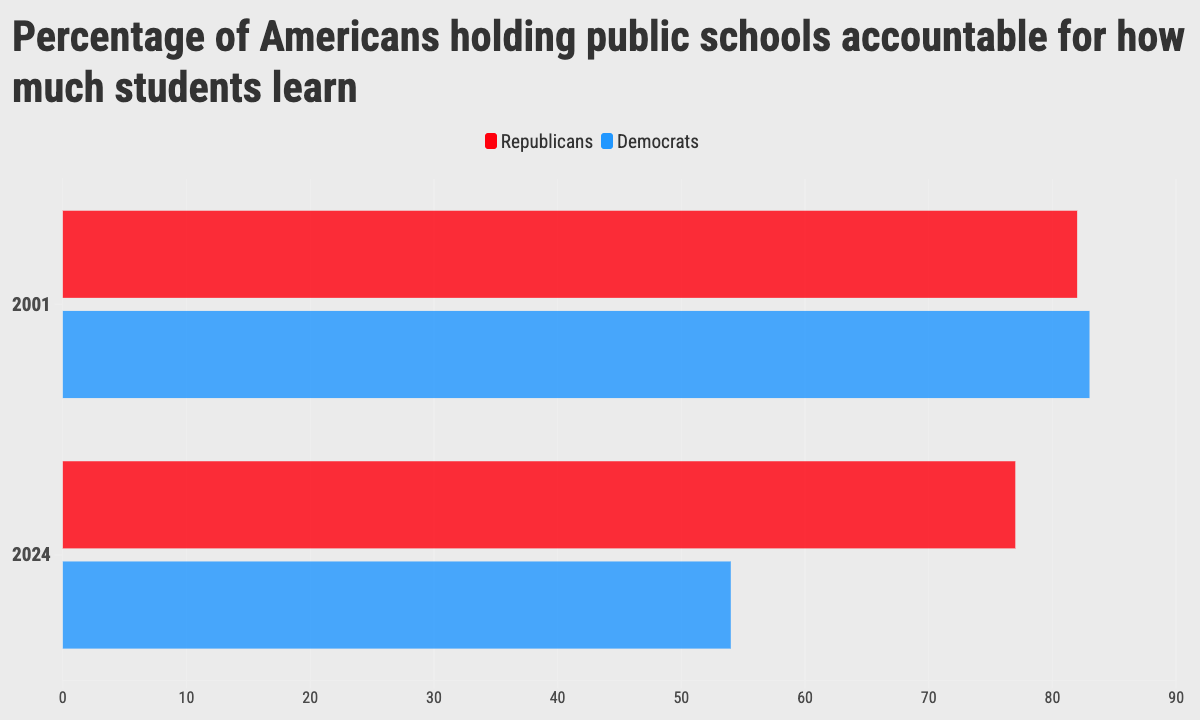

Educators and policymakers from across the political spectrum

caution

that data systems such as IPEDS and assessments like National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) are essential barometers of America’s educational health. Even Project 2025 cedes that the federal government should maintain “

statistics-gathering

” abilities in education. As funding shifts to other agencies, it’s urgent that measurement moves with the money. Efficiency without evidence is mere guesswork, and America’s children deserve better than educated guesses.

Consider NAEP, which is written into federal law as a critical audit of whether our educational systems are serving students

from all backgrounds

well. In February, the Trump administration

abruptly cancelled

the test for 17-year-olds, bucking decades of uniform collection. This decision came just days after officials had assured the public that NAEP would not be impacted by budget cuts.

A few weeks later, the department pulled the same stunt with money: A

March 28

notice suddenly ordered states to liquidate whatever was left of their pandemic-relief funds that very day, freezing

nearly $3 billion

that districts had already earmarked.

For now, pandemic relief funds

have been restored

, and for now, most of NAEP testing is back on schedule for 2026, with some conservative experts even proposing it be expanded to

an annual schedule

from a biennial schedule. But this cancel-then-revive whiplash has already forced

states and contractors to scramble

, burning scarce time and taxpayer dollars that could have gone toward students.

These disruptions are part of a broader pattern: a systematic dismantling of the nation’s education data infrastructure. Many of the staff and contractors who compile crucial K–12 databases such as the Common Core of Data (CCD) have been terminated. The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), which oversees these efforts, axed nearly everyone. Additionally, The Institute for Educational Sciences (IES) has been slashed to a staff that can’t “

even fulfill its statutory obligations

.”

While the administration promises that other agencies will disperse federal education dollars, we have received no such promise for the measurements needed to track the impact of these investments; currently, they seem to be abandoned.

All of this is happening at the worst possible time. America’s students are in an ongoing academic crisis, one that we can only grasp of national data. After the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic,

test scores plummeted

. According to NAEP results released last year, the average 13-year-old in the U.S. lost ground in both reading and math:

reading

scores fell by 4 points, and

math

scores by 9 points compared to just before the pandemic. They are now at their lowest

levels in decades

.

This is a moment when we need more educational measurement and transparency, not less. National exams like NAEP are “the canary in the coal mine,” alerting us to academic problems while there’s still time to act. Without a nationwide lens like NAEP, data warehouses as strong as the CCD and IPEDS, and research agencies dedicated to translating these results such as IES, such alarming trends couldn’t be convincingly demonstrated.

Likewise, the troves of school data that the Education Department aggregates allow educators and researchers to identify where progress is (or isn’t) happening. If those data collections halt, we’ll be stuck funding systems we can no longer evaluate, rewarding failure as easily as success.

Fragmented, inconsistent state reporting is a recipe for lost information. We’ll return to an era of patchwork statistics that can’t be compared or evaluated nationally, and the losers will be the students whose struggles are rendered invisible.

Other federal agencies certainly have the capacity to oversee large-scale, results-oriented programs. For decades, HHS has successfully administered

Head Start

, the federal early childhood education initiative. Precisely because it measures outcomes rigorously, Head Start has demonstrably improved

education, income, and health

for its participants, even now as it faces sweeping budget cuts. Similarly, HHS’s Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) has systematically tracked child insurance rates, contributing to a sharp decline in the rate of uninsured children from

14% to a historic low of 5%

. These programs succeeded because funding came paired with robust outcome measurement.

If such agencies are to steward America’s K–12 funding effectively, they must establish or absorb a dedicated educational data arm. One approach could be transferring NCES, preserving essential national assessments like NAEP and comprehensive data collections. Another might be forming an inter-agency task force specifically for education metrics. Even strong advocates of federalism recognize that comparable data across states is indispensable for judging progress; without it, monitoring becomes

uneven and incomplete.

Dismantling the Department of Education is billed as streamlining governance. But true efficiency requires more dedicated outcome tracking, not less. When schools

stopped monitoring

outcomes in the past, progress stalled and

achievement gaps widened

unnoticed.

Federal data collection has exposed inequities affecting English learners and students with disabilities, problems states were compelled to address once revealed. Removing these accountability tools risks concealing rather than solving such critical issues.

Fiscal conservatives pride themselves on demanding receipts, progressives on demanding equity. Without national metrics, both lose their yardstick, and students lose most of all.