Because it gave me a crucial safety net of security, I have appreciated higher education throughout my career. Failure was not an option in my family since we have a very strong work ethic. To survive, I had to go and improve my life and the lives of people around me. Being a first-generation Latina who completed both high school and college, I was aware that the only way I could escape poverty was to pursue higher education.

In 1981, my route to higher education led me to Rutgers University-Camden, where I currently serve as the director of the Community Leadership Center and a professor. I was able to develop the social and political capital necessary to open LEAP Academy, Camden’s first charter school, in 1997 thanks to my enrollment there. From five trailers on an abandoned lot to a complex of renovated historic buildings along Cooper Street, the school has expanded since then.

We have consistently maintained 100% high school and college graduation rates, and thousands of students have come through our doors. For 30 years, that has been our goal. In a city like Camden, where about 30% of the population lives below the poverty line and the district’s high school graduation rate is about 65%, it is an ambitious aim. There are few prospects for the future and many young people in the city are left without a diploma.

What LEAP Academy has accomplished for Camden’s students, families, and teachers makes me immensely proud. However, K–12 education is insufficient on its own. For Black and Hispanic students in particular, earning a college degree and the financial assistance required to do so is the key to true generational transformation.

To genuinely end the cycle of poverty, access to high-quality post-secondary education, career training, and a more comprehensive strategy to address systemic inequities are all required, even though a solid K–12 education lays the fundamental foundation.

I witnessed 160 Black or Hispanic students, many of whom were first-generation college students, cross the LEAP graduation stage this past June. Each one made progress toward a better future, a career, and a degree. For them, attending college represents a generational breakthrough rather than just an academic accomplishment.

How does LEAP’s strategy for college admissions operate, then?

We encourage high school graduates to finish a full schedule of college courses, remove financial hurdles for families, and set high expectations early on.

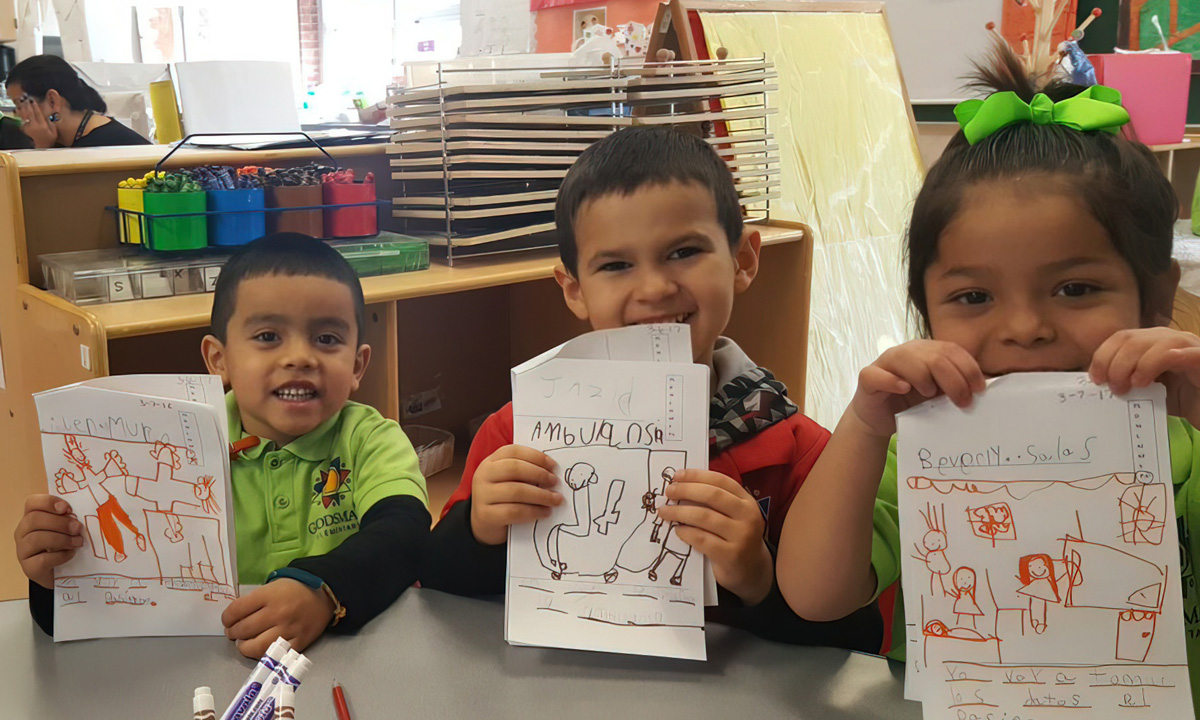

Pre-K is where LEAP begins preparing students for college. Young children can participate in an early learning program that extends into LEAP’s K–12 school with sponsorship from Rutgers University. Every year, parents contribute forty hours of their time to strengthen the school for all students. Students at LEAP attend school for ten more days than those at nearby public schools, even in the early grades. By opening our buildings at 7:15 a.m. for breakfast and remaining open until 6:15 p.m. to offer students more teaching, tutoring, extracurricular organizations, and intramural sports, we also act as a community center.

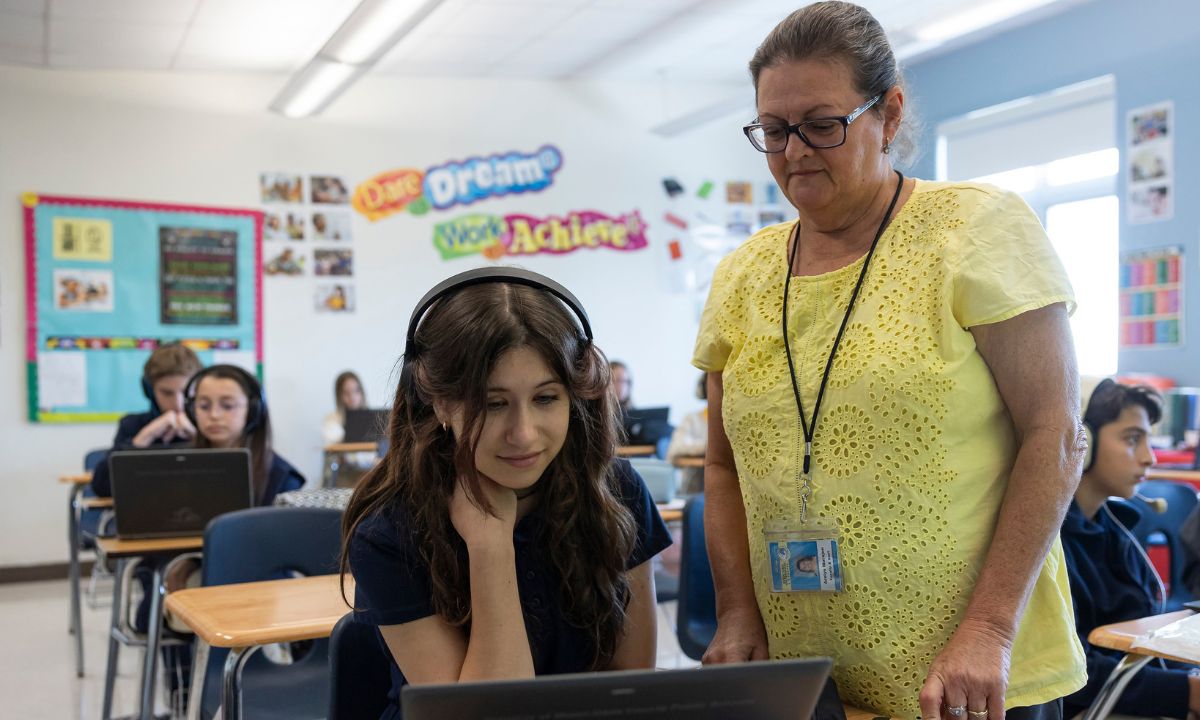

We have College Access Centers in each of our five buildings. Center staffers keep track of grades for K–8 students, explain how academic achievement relates to college preparation, and inform parents about how their children’s performance compares to college-ready skills. As high school kids are ready to apply to colleges, these services get more intense. Furthermore, the team offers programs that expose students to career options in subjects that can be pursued through college study, including STEM, law, architecture, business, and writing.

Professors from Rutgers and Rowan colleges teach actual college courses to high school students. These inner-city pupils gain valuable skills and gain greater self-assurance about their post-high school futures as a result. Rutgers-Camden graduate students tutor LEAP students throughout the school day and after school when needed, such as in challenging subjects like statistics.

More than 1,200 LEAP students have earned a full year of college credits, putting them in a position to complete their education in three years and saving families money on tuition.

Additionally, graduates who maintain a 3.5 GPA while attending LEAP, have four or fewer unexcused absences during the year, and require financial aid are eligible for full tuition reimbursement through the Alfredo and Gloria Bonilla-Santiago Endowment Scholarship. At the three campuses of Rutgers University, hundreds of students earn full tuition if they maintain a 3.0 GPA.

An other advantage is that Camden gains a wealth of intellectual capital when our students succeed in college.

It is improbable that sustainable economic investment will occur in the absence of an educated workforce. Businesses will only make investments if they think they can locate qualified, local talent. It is not a pipe dream to have a city full of college-educated residents; it is a necessity for the economy.

The population of Camden is growing, and locals are making a concerted effort to bring the city back to life. In addition to providing important services to the larger community and reviving civic pride, LEAP alumni are influencing the future of the city through expanding waterfront enterprises, nearby hospitals, and colleges.

But alarming patterns are starting to appear. Skepticism over the worth of college is increasing nationwide. Only 36% of adults, according to one survey, are confident in higher education. According to another, only 25% of respondents think obtaining a bachelor’s degree is necessary to land a well-paying job.

This degree of uncertainty is risky and foolish. Having a degree is still a criterion that managers use to assess if an applicant brings the necessary abilities to the table, even though some organizations have eliminated degree requirements from job advertising in order to demonstrate skills-based recruiting. Learning to think critically, work well with others, and widen perspectives are all important aspects of college. Students can develop their worldviews, form enduring relationships, and interact with others from diverse backgrounds there. Employers evaluate applicants against one another, and candidates with a college degree are given preference.

Undervaluing higher education runs the risk of severing the very thread that connects cities and students. To break the cycle of poverty, year-round effort and persistent commitment are needed. It requires communities that are willing to invest, families that remain involved, and instructors that have faith in their pupils.

When reforming urban areas, parents, educators, and legislators who are involved in K–12 education must never lose sight of the most important thing: giving every student the means to attain their future beyond high school and assisting them in envisioning it.