In many kindergarten classrooms, you can find children acquiring vocabulary terms through interactive read-alouds or sounding out letters in phonics lessons. The science of reading, a burgeoning effort to educate literacy using evidence-based methods, includes these scenes. And it’s working: pupils’ reading scores have significantly improved in states like Louisiana, Tennessee, and Mississippi. However, there is a genuine risk that play, which is equally important to early learning, will be sacrificed as schools strive to help young pupils acquire grade-level abilities.

Play and explicit reading instruction may appear to be mutually exclusive at first. In order to make time for instruction, schools may reduce recessive imaginative activities in response to pressure to improve reading outcomes following years of declining or stable scores. However, this is a mistaken decision.According to research, play is not only in line with the science of reading, but it is also an effective means of helping children develop the same abilities they need to become proficient readers in the first place. In actuality, children learn best when they are actively involved in activities that help them retain new words and sounds.

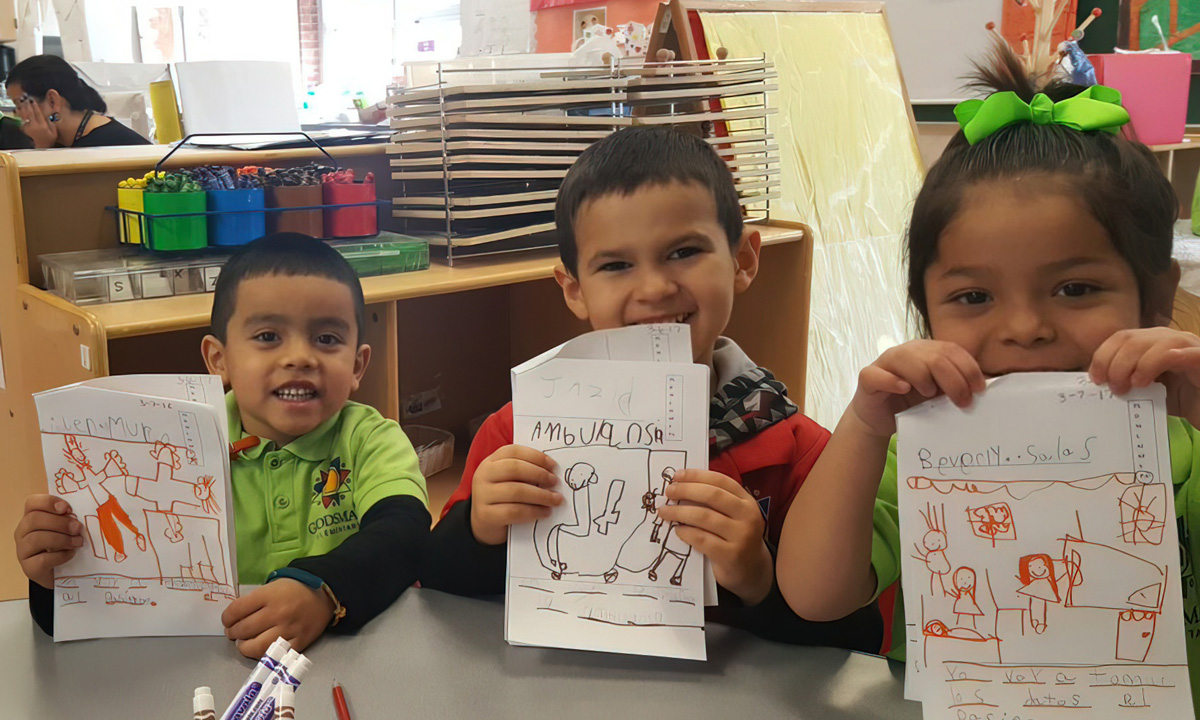

This is due to the fact that play is important learning and not just fun.For young children in particular, guided play—where teachers put up enjoyable activities with specific learning objectives—is more successful than direct instruction at fostering learning. For example, research has shown that teaching literacy through activities like blocks, painting, and dramatic play enhances children’s oral language, letter recognition, and the capacity to sound out words and letter blends. For children, learning to read was like playing a game, but the benefits were genuine.

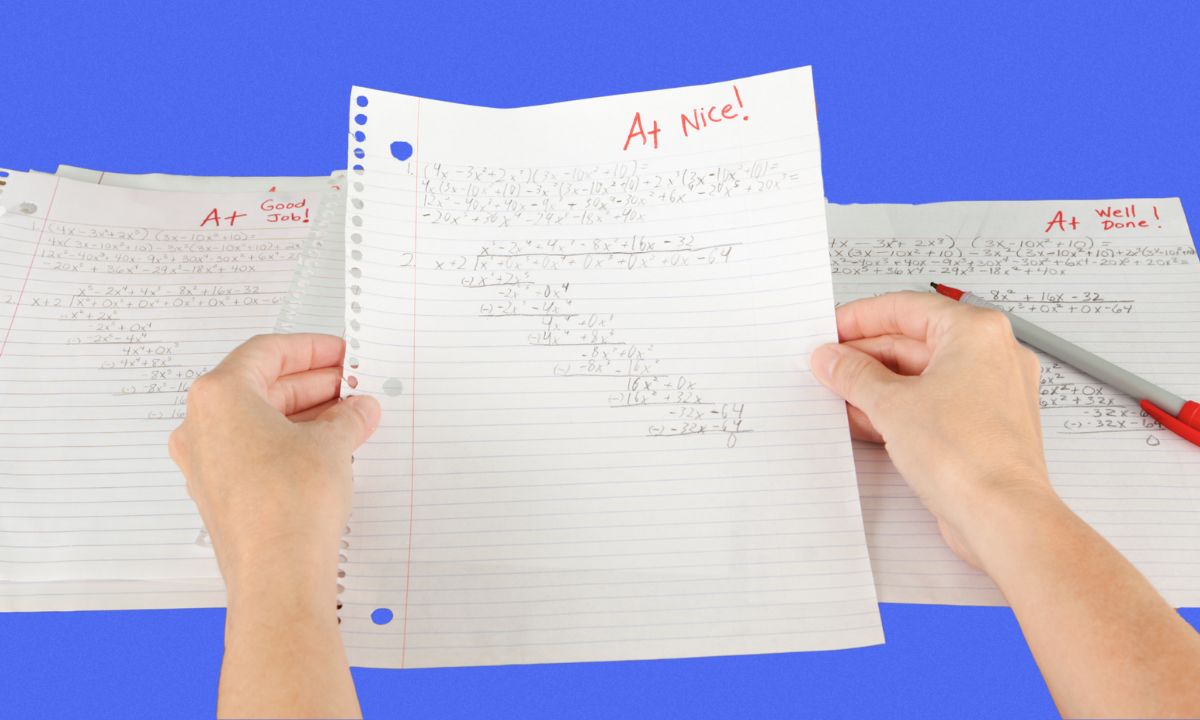

This can be implemented at scale, as demonstrated by the Boston Public Schools’ evidence-based Focus on Early Learning program. Pre-K through second-graders there spend the most of the mornings enacting stories, playing with letters, and perusing books—all of which are meticulously organized by teachers to conform to the principles of the science of reading. Boston has made a play-based approach the main focus of K–2 education, in contrast to many districts that have changed early grade instruction to be more typically academic. The outcomes demonstrate its effectiveness:Compared to their counterparts who are not enrolled, students in the program routinely demonstrate much higher literacy and language proficiency.

Programs like Every Child Ready and Tools of the Mind are being implemented in districts around the country. For instance, a Tools pre-K classroom employs themed dramatic play to teach early reading skills. In a make-believe grocery store, kids can make shopping lists (writing), categorize products (vocabulary), and discuss supper ideas with their peers (language development). Every Child Ready classes teach letters and sounds using games, stories, and songs. Teachers keep a close eye on students’ progress so they may adjust their education. These methods help kids acquire the skills they need to be prepared for kindergarten by fusing the greatest aspects of disciplined reading with fun learning. Research indicates that kindergarteners in Tools of the Mind significantly improve their self-regulation and social skills, while children in Every Child Ready outperform their classmates on core literacy abilities.

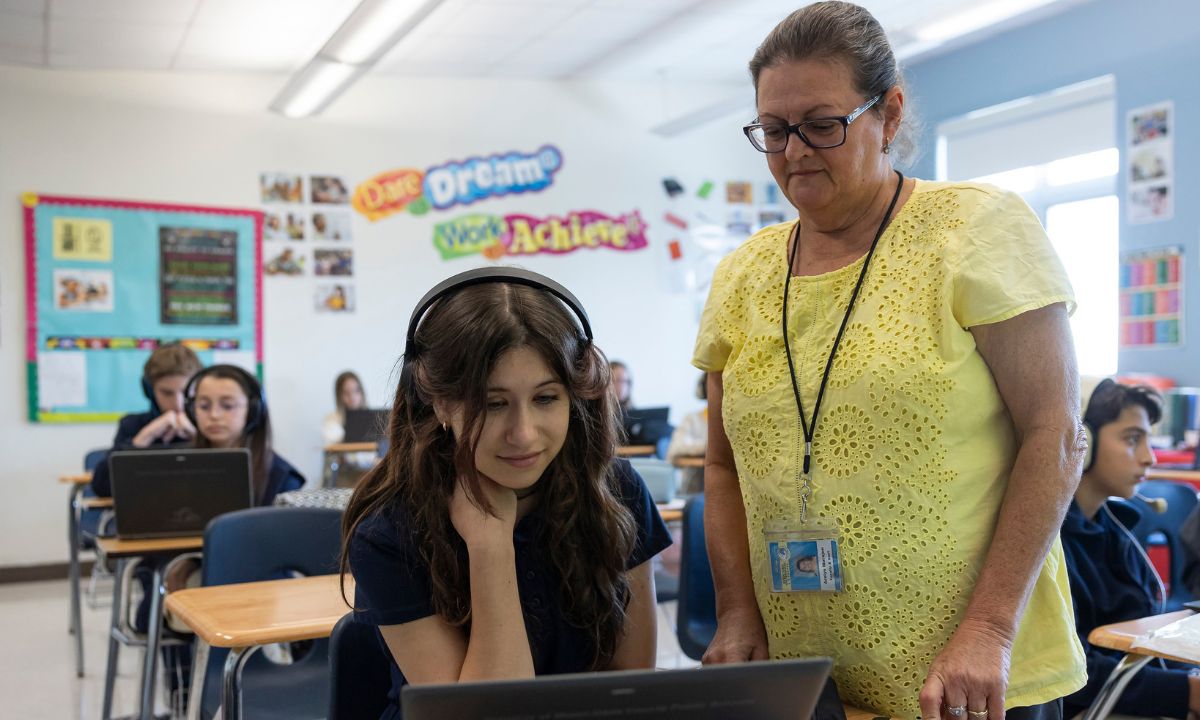

Boys and kids in schools with a high proportion of low-income students may benefit most from this combination of play and research-based reading instruction. Many boys, particularly those who are among the youngest in their grade, find it more difficult to learn as a result of the shift in instruction toward more sit-still-and-listen exercises. Boys can benefit from early learning engagement through play-based techniques, which provide greater mobility and choice, strengthening their foundation for future academic performance and literacy.

As schools strive to raise test scores, low-income children—who are already less likely than their wealthier counterparts to have access to high-quality play opportunities—often lose out on this little play time first. Schools may be unwittingly depriving children of one of the most useful and scientifically supported tools in their toolboxes if they move away from play.

America’s literacy gap must be addressed since two-thirds of fourth graders in the country are not proficient readers. However, converting early learning into a set of exercises and worksheets is not the solution. Play is essential to fostering a love of learning. The creativity, joy, and social development that are essential to the early years shouldn’t and need not be sacrificed for reading success.

Policymakers and education leaders should support evidence-based training, evaluations, and curricula that incorporate play and reading. You’ll see benefits if you assist teachers in making literacy instruction fun and interesting and allow children to freely explore and imagine while they learn.

The 74