Universities and colleges are having a hard time surviving.

There are several reasons for this, including a decline in the number of students in many parts of the country who are of college age, rising tuition at public universities as state support decreases, and a growing lack of confidence in the worth of a college degree.

There is growing pressure to save expenses by shortening the four-year degree program to three years.

Return on investment and degrees that are more likely to result in meaningful employment are becoming more and more important to students, parents, and lawmakers. There is now an imbalance between supply and demand as a result of increased enrollment in professional programs and decreased interest in traditional liberal arts and humanities majors.

As a result, there is now more financial strain and a record number of mergers and closures, primarily among smaller liberal arts colleges.

Institutions are rushing to match curriculum to market demand in order to survive. And in order to accomplish this, they are turning to the conventional college major.

The main criterion for academic excellence and institutional effectiveness is still the college major, which is created and taught by disciplinary specialists in separate departments.

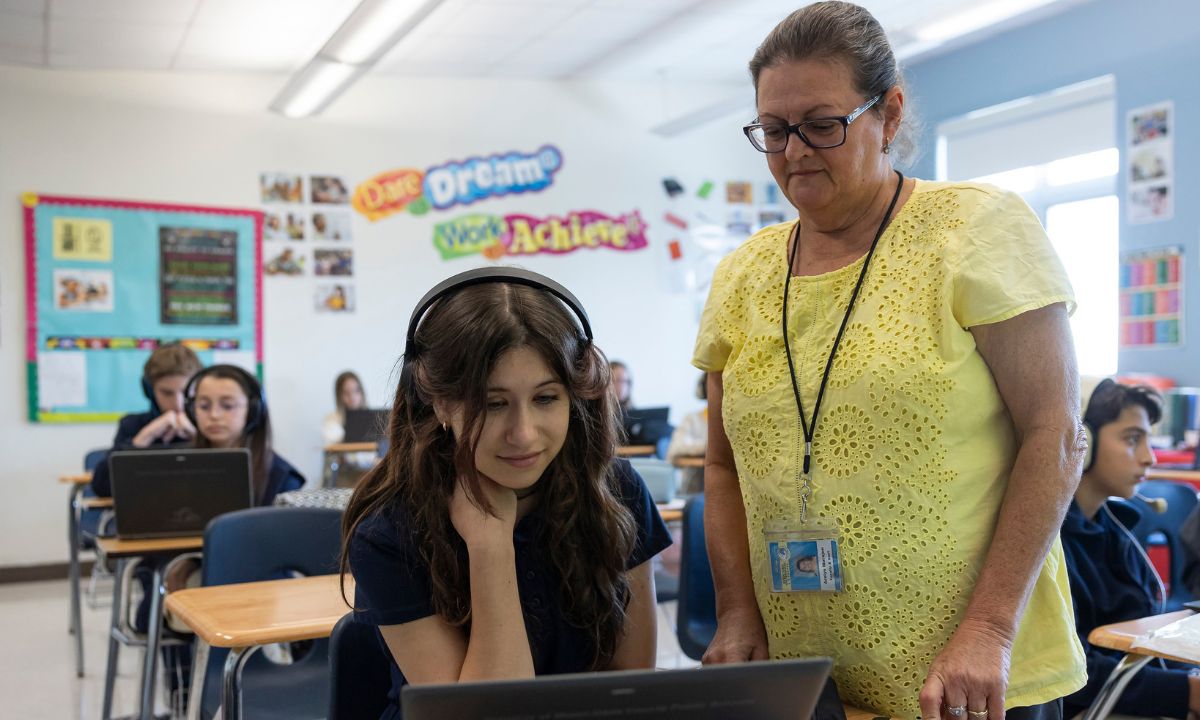

For professional majors that are more closely related to employment or that are regulated by accreditation or licensure, this arrangement probably works well. However, relying solely on the discipline-specific major may not necessarily benefit students or institutions in the rapidly changing landscape of today.

I contend that the college major may no longer be able to keep up with the combinations of skills that span multiple academic disciplines and career readiness skills that employers demand, or the flexibility students need to best position themselves for the workplace, as a professor emeritus, former college administrator, and dean.

Students want flexibility

Every year, I witness students coming to college with a variety of passions, interests, and skills, ready to weave them into fulfilling lives and careers.

Student success is correlated with a more flexible curriculum, and students now use ChatGPT and other AI technologies to determine which course combinations will best prepare them for the future. They desire freedom, autonomy, and time to refocus their studies if necessary.

However, students are prompted to select a major from a list of preset and recommended options as soon as they get to campus, even before they apply. The major creates an academic route that is anything from flexible when combined with general education and other college requirements.

Approximately 80% of college students change their major at least once, which is not unexpected given that more flexible degree requirements would enable students to mix and explore a variety of interests. Furthermore, as technological change becomes more disruptive, the number of careers—let alone jobs—that college graduates are required to possess will only rise.

The college major is still the primary metric for attracting students and balancing finances, therefore the curriculum may be less flexible now than it has ever been.

How schools are responding

Colleges are adding new, in-demand programs at a record rate in response to market demands. While enrollment climbed only 8% between 2002 and 2022, the number of degree programs nationwide expanded by approximately 23,000, or 40%. It may be argued that some of these majors—like cybersecurity, fashion business, or entertainment design—connect disciplines rather than distinguish themselves. As a result, these new majors compete with comparable new majors at rival universities and divert enrollment from less popular programs inside the university.

In an effort to draw students and boost employability, traditional arts and humanities majors are also introducing professional courses. However, this duplicates curriculum already available in other areas and adds credit hours to the degree.

Crucially, few programs are eliminated even as new ones are established. Along with the conventional belief that faculty members establish the curriculum as subject-matter experts, the problem is in faculty tenure and governance. This makes it challenging to redirect resources to areas of growth and cancel or update programs with little demand.

Underenrolled programs, cancelled courses, and overstretched resources result in a proliferation of these issues, which lowers program quality and lowers teacher morale.

Ironically, there may be perverse incentives to increase the number of credit hours needed for a major or general education requirements in order to obtain more funding or introduce courses that fit faculty interests when demand is down. All of which emphasizes the resources that are available and keeps broadening the curriculum.

Universities are likewise struggling with how to bundle the general education requirement and the concept of liberal education.

Despite growing criticism, businesses and students continue to appreciate liberal education.

Students’ skills for career readinessTheir capacity for critical and creative thought, productive teamwork, and effective communication continue to be powerful indicators of future success in both the job and in life.

Reenvisioning the college major

Colleges may permit students to combine smaller modules, such as variable-credit minors, certifications, or course sequences, into a customisable modular major, provided that students must finish a major in order to receive a degree.

This enables students to choose from a variety of subjects and, under the direction of advisers, put together a degree that suits their interests and objectives. Everything can be brought together and given context with a few project-based courses.

Existing majors where demand is high would not be threatened by such a paradigm. In others, where enrollment in the major is dwindling, a flexible structure would increase enrollment, retain faculty expertise rather than eliminate it, draw in more nontraditional students who bring credentials they have already earned to campus, and improve the bottom line by aligning the curriculum with student demand.

The combination of curricular content is what gives such a flexible major depth, despite the criticism that it lacks study depth. The inability to successfully promote it to employers is another critique. To showcase students’ distinct skill sets, however, a customized major can be labeled and communicated to employers in a clear and concise manner.

Furthermore, extracurricular activities including study abroad, internships, undergraduate research, and organizational leadership can be accepted as modules in a flexible curriculum as more and more students attempt to incorporate them into their academic programs.

It’s important to note that although a number of universities offer interdisciplinary studies majors, these are either overly restrictive or deny students access to courses that are in high demand. The success of a flexible-degree model would depend on the availability of course parts that may be added or removed in response to student demand.

Additionally, a number of institutions now provide microcredentials, skill-based courses, or course modules that increasingly incorporate liberal arts courses. However, these usually need to be finished in addition to the major’s requirements.

The college major is something we take for granted.

However, it’s important to remember that the major is a very new invention.

Prior to the 20th century, students studied a wide range of liberal arts subjects in an effort to produce people who were well-rounded and open-minded. In response to a changing workforce that valued specialized expertise, the major was created. However, the model is subject to change as times do.