According to a recent assessment, the pandemic’s consequences are still being felt by American children and teenagers, and the majority of pupils of color are suffering from worsening or stagnating indications.

While there are some positive trends nationwide compared to 2019, such as an increase in the number of children with health insurance and a decline in adolescent pregnancies, the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s annual Kids Count report, which was released last month, revealed that many states are having difficulty caring for their children, whether it be in terms of the number of children living in poverty, the rising number of teen deaths, or the number of older students who are not enrolled in school or working.

According to Nicholas Munyan-Penney, assistant director of P-12 policy at EdTrust, a national education policygroup and Annie E. Casey Foundation grantee, the total figures paint a somewhat ambiguous picture. However, when we look at it by demographics, we find that there are still significant differences between racial groupings, especially when it comes to the educational outcomes of Black and Latino kids.

According to the research, seven out of 16 measures showed progress on a national level. Three of the remaining metrics stayed the same, while six have gotten worse since 2019. However, American Indian, Alaska Native, Black, and Latino children performed worse than the national average in nearly all 16 categories.

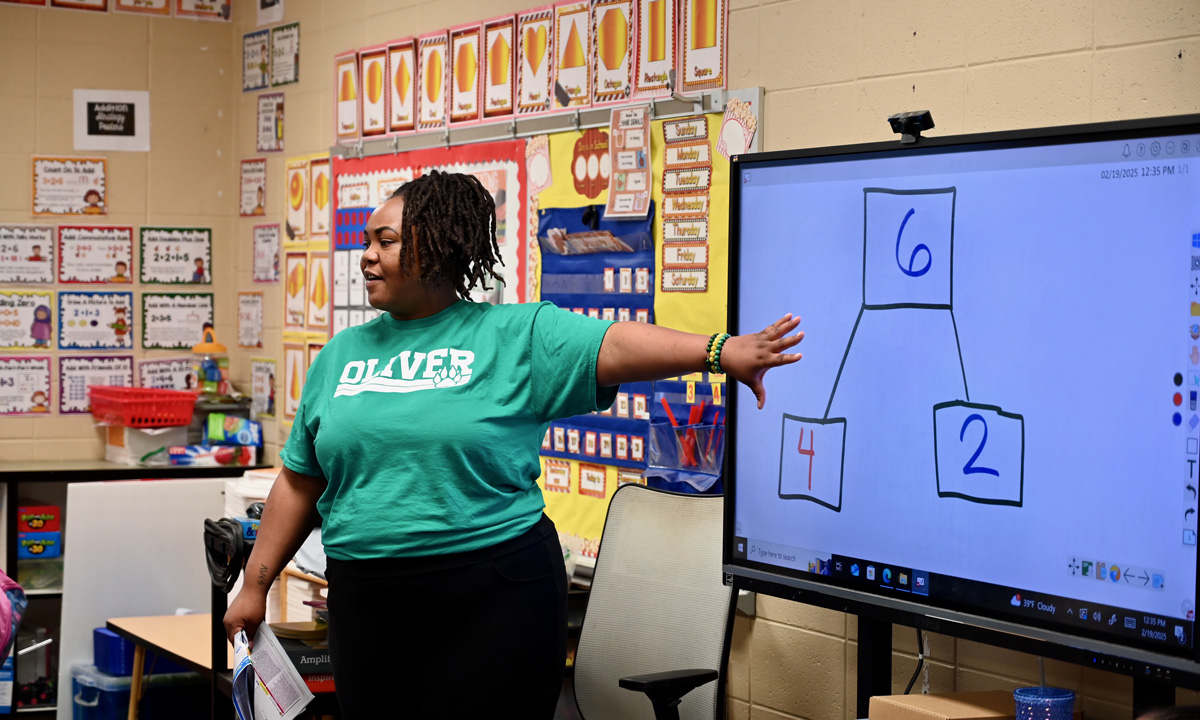

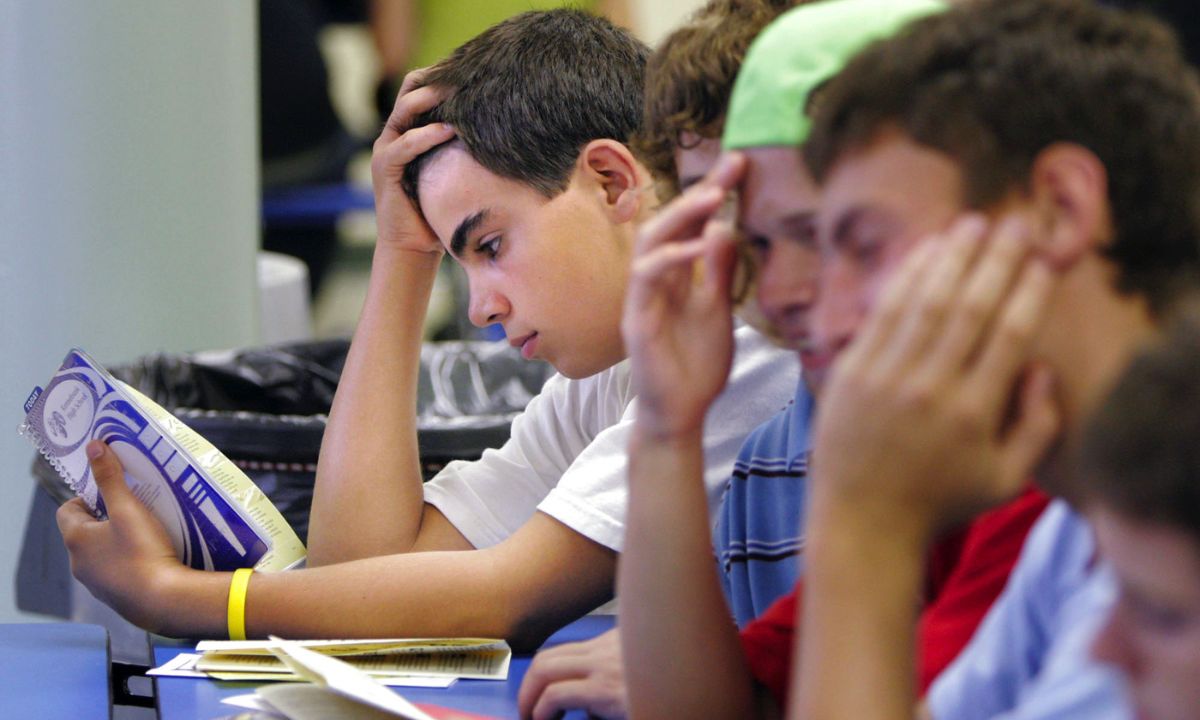

According to the research, education had the worst recovery in recent years, with fewer children nationwide attending preschool and ongoing drops in reading and math performance for all demographic groups between 2019 and 2024.

In 2024, 70% of American fourth graders were not reading at grade level, up from 66% in 2019, according to the analysis, which used federal NAEP test data from the National Center for Education Statistics. This effectively reversed ten years of improvement. Additionally, roughly 73% of eighth graders struggle in arithmetic.

When compared to their white and Asian peers and the national average, the gaps between Black, American Indian, Alaska Native, and Latino kids grew. For instance, compared to 61% of white fourth students and 63% of white eighth graders, approximately 84% of Black fourth graders and 90% of Black eighth pupils, respectively, did not perform on grade level in reading and arithmetic in 2024.

Between 2018–19 and 2021–22, high school graduation rates nationwide rose by one percentage point to 87%; however, as with proficiency, the majority of pupils of color fall four to 13 percentage points short of the national norm.

According to Munyan-Penney, this is a clear indication of the fact that students have received disproportionate resources for many generations. The data provided clearly supports our knowledge that low-income and pupils of color have consistently seen less investment in their neighborhoods and schools.

In 2019–23, a disproportionate number of children of color lived in high-poverty areas: 20% of Black and American Indian or Alaska Native children and 11% of Latino children lived in concentrated poverty areas, while just 3% of white, Asian, and Pacific Islander children did the same.

According to Munyan-Penney, there is frequently a direct link between concentrated poverty and poor student accomplishment because the majority of states use local property taxes to pay public schools.

Beyond education, disparities also existed, especially when considering the rate of child and teen fatalities per 100,000.

The number of children and young people aged one to 19 who passed away per 100,000 rose from 25 to 29 between 2019 and 2023, with accidents, killings, and suicides accounting for the majority of these deaths. Between 2019 and 2023, the number of Black juvenile deaths increased by 30%, from 41 to 53 deaths per 100,000, making it nearly double the national average.

The welfare of children has also been a fluctuating aim on a state-by-state basis.

Mississippi, Louisiana, and New Mexico received the lowest scores for overall child well-being, while New Hampshire, Vermont, and Massachusetts were at the top of the list. The research recognized that, in spite of overall rankings, several states have wildly disparate scores across categories. For example, North Dakota, which ranked first in economic well-being but 42nd in education, and Maine, which scored 17th overall but 41st in education.

According to the analysis, impressive state-level results can conceal the fact that millions of individual kids are still having difficulty accessing the services.

The research attributed improvements in parental employment and children’s health insurance coverage to federal investments in healthcare coverage and economic stability during the pandemic.

Between 2019 and 2023, the percentage of children with a parent without steady work improved by one percentage point, to about 25%. According to the study, family financial stability was strengthened by financial assistance, such as an enlarged child tax credit and pandemic relief funds in 2020–21. Additionally, the survey revealed that the percentage of children with health insurance increased from 5% in 2019 to 6% in 2023, which was a positive development.

However, given the expiration of some pandemic-era programs and recent cuts to SNAP and Medicaid by President Donald Trump’s administration, these achievements may also be in threat in the years to come.

“I am very concerned about the reduction in federal investment,” Munyan-Penney stated. It seems unlikely that these figures will continue to rise unless there is a significant shift in the federal government’s policy or significant state investment.